THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR movement cites the 1891 Queensland Shearers’ Strike as a milestone in its establishment, giving credit to the thousands of shearers who marched for fair wages and conditions at Barcaldine that year. Yet an earlier industrial dispute in the New England region showed that signs of unrest were stirring a decade prior.

Apart from mentions in contemporary reports from the 1880s, there is little evidence of this strike that impacted the building of the Great Northern Railway line between Deepwater and Bolivia, ten kilometres to the north.

There, on Ngoorabul Country, a significant town was raised at the foot of Bolivia Hill to house the people who built the railway line. Thanks to journalists, we can glimpse the life that once buzzed around Bolivia, get details about the construction of an engineering feat, and understand the tenuous nature of the workplace at the peak of the Victorian era.

‘Hopeless bogs and gluepots’

Even before the Great Northern Railway reached Glen Innes in 1884, construction of the line northwards to Tenterfield had been contracted to Cobb and Co, the renowned coaching business that had foreseen the end of its core business with the spread of the railways, and diversified into building transport infrastructure.

The carriage of passengers on daily coach runs north and south through this difficult stretch of country meant the company can have been under no illusions about the terrain of Bolivia Hill:

“The hill is very steep, and though the road is good, it is dreaded by teamsters, for the pull up the ascent is long and heavy.”

Australian Town and Country Journal, September 1883

A Cobb & Co traveller ‘EJW’ provided the perspective of a coach passenger:

“From Bolivia to Glen Innes the road was a sore one to travel. Continuous and heavy rains had fallen for weeks, and the traffic incidental to railway construction had cut up the track in every direction – so much so that the coaches on each daily trip are compelled to make a new one through the bush, only to find on returning that teams have followed them and dotted it with hopeless bogs and gluepots.”

The Queenslander, March 1883

The railway was going to conquer this arduous incline, but it would take an army of navvies, the much-demonised brawn of the Industrial Revolution.

‘This sylvan village’

Thought to be a shortening of ‘navigator’, navvies were manual labourers who built canals, railways and roads from the 18th to the 20th centuries across Britain and its colonies. Much of the media coverage and literature from this era treats this class of men with a patrician disdain, assuming drunkenness, laziness and questionable morals around sly grog-filled shanty towns. Despite reports of some ruffians, travellers would have received a warm welcome in Bolivia, which from multiple eyewitness accounts was much more than a temporary community by 1883:

“Here, on the eastern side of the railway line, the company [Cobb & Co] have erected their offices, workshops, and stables; there is also in the camp a post and telegraph office. On the opposite side of the line is the township, extending along the gully at the foot of Bolivia hill. Through the township, and over Bolivia hill runs the main road from Glen Innes to Tenterfield… The township is formed on either side of the road for about a quarter of a mile.”

Australian Town and Country Journal, September 1883

The same article lists two hotels, two bakeries, two butcher’s shops, two general stores, two produce stores, two tobacconists, multiple “fancy goods” businesses, a saddler, a bootmaker, “half a dozen or so” boarding houses, and one barber’s shop run by a man who might have been Indigenous judging by the archaic description.

The use of the word “township” is a clue that this place was much more than a navvies’ camp, and the writer of this article goes into great detail about other signs of permanence:

“Some 50 or 60 private dwellings, some of canvas, and others constructed of bark, complete the village; certainly the inhabitants cannot complain of an absence of business houses at which all their wants may be supplied. Contentment seems to reign in this sylvan village and many of the men, knowing that the work to be had would last some time, have made their wives and families as comfortable as circumstances permit, and through the open door one may see the prosperous navvy (a navvy may be prosperous if he doesn’t drink, for he is in receipt of good wages) taking his noonday meal off a clean table cloth covering a substantially laden board; or after the meal taking his smoke before assuming work for the afternoon, and beguiling the time with fondling the baby while his wife clears away the dishes.”

Australian Town and Country Journal, September 1883

Two months later, another un-named journalist visited Bolivia and observed Chinese migrants growing vegetables, “right in the centre of the township”, and interviewed residents who were looking to their town’s future:

“The principal grievance of parents is the absence of schooling for the children. We trust, however, that the steps now being taken by the inhabitants in this direction will result in attainment of the desired object shortly.”

The Armidale Express, November 1883

A school did indeed get raised, although life in Bolivia came with a constant reminder of the town’s purpose.

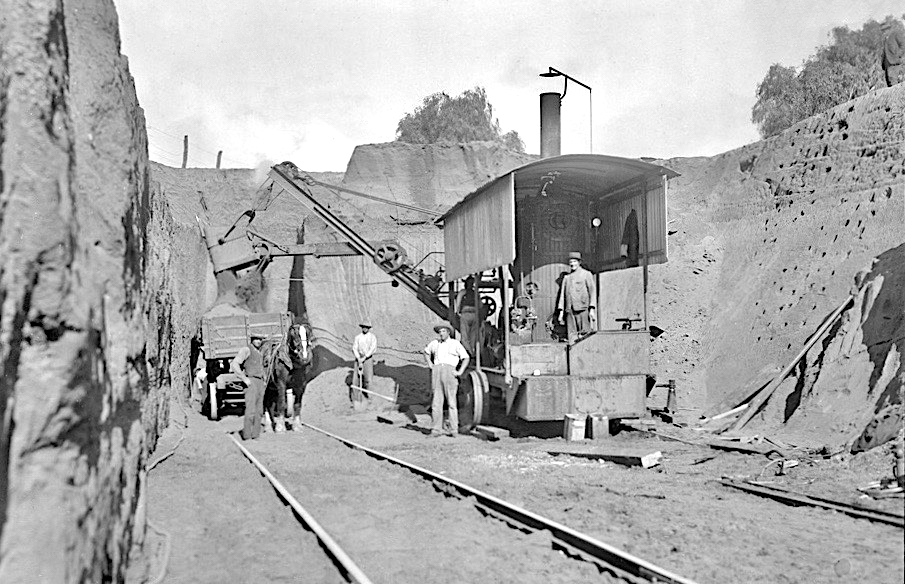

‘Debris hurled into the air’

Constructing the railway line from Glen Innes to Deepwater was a relatively easy process compared to the cutting of the corridor through and down Bolivia Hill. The Australian Town and Country Journal reporter (September 8, 1883) indicated that just one of the cuttings required the removal of “75,000 cubic yards of granite”:

“Beyond this is the spot known as the Horse-shoo Bend, where the line is compelled by the nature of the country to take a sweep round half a circle on the sides of the hills, forming the shape as described in the name given the place.”

Then there was the startling use of blasting powder, usually at noon or at five o’clock in the afternoon when the navvies downed tools:

“By this arrangement no time is lost in stopping the work to enable the men to get out of the way of the falling stones and debris hurled into the air by the force of the discharges. When, as frequently happens, a number of these shots take place in succession, one can almost imagine the reports are from heavy cannon, so great is the shock. Then the sound is taken up by the surrounding hills and goes echoing off from crag to crag, producing an effect as impressive as it is startling to the unwary.”

Such accounts give a sense of structure in the demarcation of work hours, although there were signs of mounting pressure, with work on the line being “pushed”:

“The difficulties to be overcome are of no ordinary character. The cartage and haulage can be but slowly performed, owing to the steepness of the road in places; it is no uncommon sight to see as many as 14 or even 18 horses drawing a load that on roads in ordinary country might be taken by six. Under these circumstances work is necessarily slower than it would be with more favourable conditions.”

Christmas and New Year came and went in the ‘sylvan village’, but before Easter, it was feared that all hell might break loose.

‘The Mob’

A navvy’s pay on the Great Northern Railway construction from Armidale to Glen Innes was advertised as a shilling an hour for 600 “pick and shovel men”, and 100 “hammer and drill men” earned that as a minimum.

Years of construction work had cost the New South Wales colonial government so much that by the time the final northern sections of the corridor were built, ironbark and brick bridges and viaducts were raised instead of the iron structures more common to the south.

But the biggest explosion heard around Bolivia in February 1884 came with the sudden upsetting of the status quo.

“On Tuesday the Hill was in rather unusual commotion, when, about 11 o’clock, the noise and shouting of a large body of men and boys was heard coming up along the line from the Horseshoe Bend. It was, however, soon apparent what was the matter, when the workmen in the neighbouring cuttings were seen to knock off. It was the mob, most of whom had come along from Tenterfield way, calling at every cutting and demanding all hands to cease work and ‘go on strike’ for higher wages.”

Glen Innes Examiner, February 1884

This wasn’t quite the whole story, which would become apparent a fortnight later. The navvies had, in fact, mobilised swiftly to meet publicly and spread the word to the media about a proposed cut in their wages.

The Bolivia section manager since early 1883 was a Mr F. Mason, who resided in the town, although the same report placed him in Sydney at the time of the industrial action. His absence possibly accounted for what took place next.

Tools were downed on Tuesday February 5, 1884 and a meeting called, to which men “marched with music”:

“An open air meeting was held at the Horseshoe Bend on Wednesday night, when a committee was formed and members deputed to traverse the section north and south for the purpose of preventing a resumption of operations until the demands of the navvies are acceded to.”

The Armidale Express, February 1884

By Saturday February 9, the local media reported, “all work between Tenterfield and Deepwater is at a standstill”.

Navvies’ pay day was Saturdays, and since most reports predicted, “an extensive exodus of employees for ‘fresh fields and pastures new’,” there was a sense that when the pay cart arrived from Glen Innes it would be bearing less wages for an angry crowd.

To see for themselves, the mob walked from Bolivia to Deepwater.

‘As silent as the grave in the cuttings’

“So far, every thing has been carried on quietly, and no depredations of importance committed,” the Tenterfield Star reported of the strike’s first Saturday payday, but a week later, with tools still down, news of the strike had reached Sydney, with a significantly different account of the pay issue:

“Matters along the railway line during the past week have been rendered very lively by a strike amongst the navvies. It was intimated by Messrs. Cobb and Co. that the wages would be reduced from 8s. per diem to 7s. 6d, on Monday… all is silent as the grave in the cuttings; but not so at the public-houses, where high revel is held, and will be until all money is spent. That will not take long, so that most of the men will, it is thought, accept the lower rate and resume work, especially as work is not quite so plentiful as it has been, and numbers of men are prepared to come over from Queensland and fill the vacant places.”

The Sydney Mail February 1884

A week later, Deepwater’s pubs were still busy ahead of the next paycart:

“The navvies on strike on Messrs. Cobb and Co’s contract were very quiet until today. Some however: have now begun drinking, and it is feared that they will start damaging property. A telegram was received from Bolivia, applying for an additional number of policemen to accompany the paycart, which is leaving Glen Innes tonight.”

Australian Town and Country Journal, March 1884

According to the The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser report, Cobb & Co was determined to make a stand, and, “a good deal of sympathy is evinced towards them.”

Just what that paycart contained by way of wages appears to be lost from the record.

‘The loquacious navvy’

By the middle of March, the media was reporting the end of Bolivia’s industrial action:

“The strike is over from here to Glen Innes; for the last fortnight all the works have been in full operation. It was a well organised affair, but it failed in its object. The contractors will suffer little, if at all. The storekeepers on the line, the business people in the townships, and the navvies themselves are the heaviest losers by the movement. Men are now plentiful, and in a very short time every gang from Glen Innes to Tenterfield will be made up to its full strength. The strike on Cobb and Co’s works will soon be but a memory of the past and theme for the loquacious navvy to dilate upon by the camp fire or the public house-bar.”

The Armidale Express, March 1884

A year later, a navvy strike in Queensland on a section of the Southern and Western railway was reported in Rockhampton’s Morning Bulletin, outlining the summons of a strike leader who was ultimately ordered to pay almost 30 pounds in fines and costs for obstructing a railway ganger, likely his boss. This was an escalation on the tactics used to break the Bolivia strike, foreshadowing the police responses that met the Queensland shearer’s strike six years later.

A snippet at the end of the same report suggests the kind of outcome that may have been brokered at Bolivia and kept out of the media so as not to inspire other strikes:

“A recent telegram mentions that the strike is at an end and we must, therefore, conclude that an amicable arrangement was arrived at.”

Morning Bulletin, Rockhampton, April 1885

Amicable outcome or not, the railway service to Tenterfield opened in 1886. At a banquet in that station’s goods shed on the afternoon of October 19, attended by several northern NSW luminaries (yet boycotted by just as many others), the responses to Governor Lord Carrington’s opening speech were peppered with bitter to-and-fro about political interference in the Great Northern Railway’s construction.

It had been a hard-fought project, yet even with just 12 miles to connect the line to Wallangara on the Queensland border, the response of NSW Commissioner of Railways Charles Goodchap ruminated on the “extravagance” of the works:

“It was said we had too many men employed.”

The Maitland Mercury, October 1886

Lord Carrington answered the unruly dignitaries with a toast to the prosperity of Tenterfield. Lady Carrington, the “ladies of the Colony”, and the press, also had glasses raised to them, before the gathering retired to prepare for an evening ball.

The navvies, who – according to Goodchap – had built 900 miles of railways in the state over the previous 25 years, didn’t rate a mention.

This article was first published in the Glen Innes & District Historical Society’s annual Bulletin, 2024.