A Writer returns to the scene of the crime.

MORE than 20 years after my family moved away from the country town of Inverell, leaving behind failed dreams and a broken marriage, I returned on a rainy evening in late 2003 with some unfinished business.

I’d called ahead to my grandmother, who was still living there in a nursing home. Before taking her to lunch the next day, I dropped into the local courthouse, an imposing clock tower at the centre of town, where a helpful woman proceeded to assist me in finding my mother’s name in the court records.

The court staffer didn’t flinch when it quickly became apparent we were not looking for a plaintiff of any kind, but rather a defendant. Trouble was, I had no specific dates to search, only the barest clues from what I’d been told about mum’s appearance in the court on a shoplifting charge sometime in the 1970s.

That meant mum’s name was still on the police computer database, in which the dates became brutally clear: just before Christmas, 1977, the police had made their way to our property off the Bingara Road, with complaints from two Inverell shops that mum had stolen childrens’ clothing and kitchen implements.

All court records prior to 1980 were stored in the archives of the New England University at the nearby city of Armidale. Would I like them faxed over? I agreed to return to the police station adjacent to the courthouse when they were ready.

Next, I dropped into the council chambers with a request. I had in my possession a hand-sized flat stone which had been picked up off the driveway of our farm, a flint-like rock with a broad space for a thumb to hold the sharpened edge to use it for cutting – an aboriginal hand axe of indeterminate age.

I asked if there was any kind of Aboriginal cultural heritage centre, or perhaps a museum, which would be interested in taking this stone tool off my hands?

The council staffer held her gaze with an open, shocked mouth, and shook her head, muttering “no…,” and, “good luck with that,” before leaving.

The tourist information centre had the name of an Aboriginal elder who lived locally. I drove the streets of our old neighbourhood searching for the address, but there was no-one home, and the only Aboriginal public office was well and truly closed.

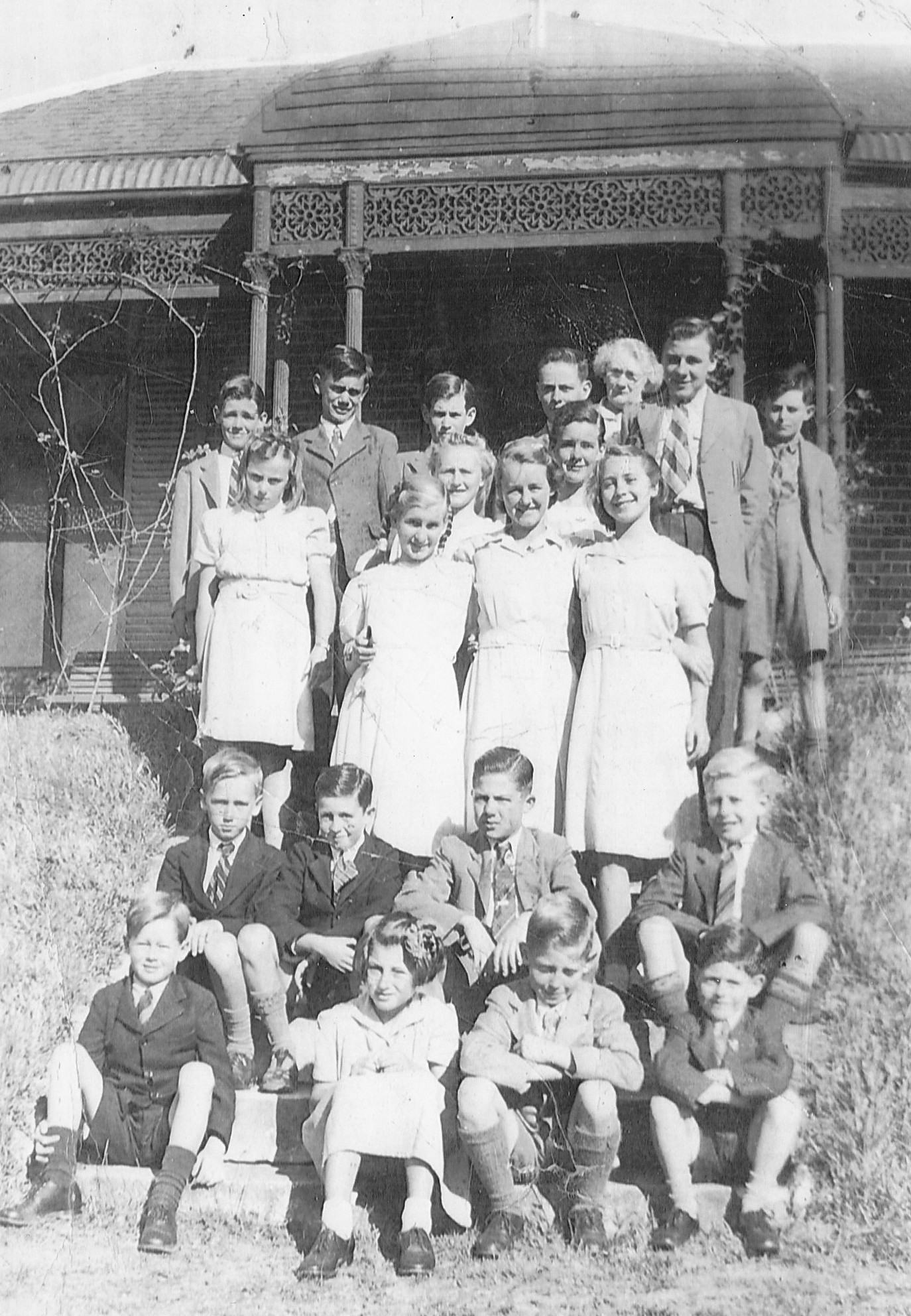

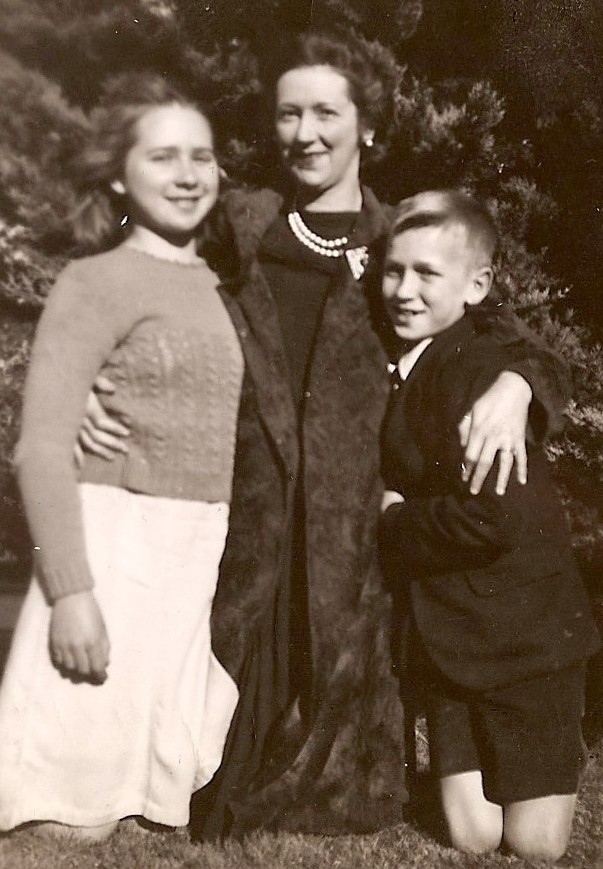

I began to wonder whether the stories I’d been told about this stone were true, or if they’d been elaborated into family myths? I had taken it to school for ‘show and tell’, with the family name written on it using thick black marker pen in my mother’s hand. She was interested in anthropology, and we had inherited all kinds of fossils and artefacts at her death at decade before.

But on returning to the riverside shopping centre to buy grandma a present, my doubts were allayed by the wall built of local stone at the gateway, the very same blue, brown and ochre basalt. The wall was all that remained of the department store built by my ancestors in the town. I knew then I had the right rock back in the right region.

Grandma was dressed and eager to get out and about, waiting for me outside the door of the nursing home. We laughed as I lifted her into the passenger seat of my four-wheel drive, me allaying any embarrassment she felt by reminding her of the hundreds of times she had lifted me into a car when I was a child.

We had a lovely lunch. She enjoyed the meal and hearing all my news about life in the big city. We’d corresponded about family stuff many times, and it seemed a waste of time to go over it all again – she and I had come to terms already. We loved one another, that’s all that mattered.

I dropped her home when she started to tire, and headed out of town, along a well-trodden road into the uplands south west of Delungra, where fields of wheat in black soil run for miles and miles under enormous skies.

I’d met the present owner a few years before, but I hadn’t come to see the house again. I’d picked-over the traces of my family’s dream many times before: the room where my baby brother died, and the hopeful imprint my parents had made on a property which was derelict when they moved there.

I looked over the stones on the driveway, and sure enough, scattered along the verges were more of those flinty fragments like the larger one in my pocket.

I was headed a few kilometres further west, to a lonely place on the Bingara Road, where a memorial had been built in the year 2000 to the Aboriginal men, women and children who were slaughtered on a hillside in 1838 at the hands of European settlers in what came to be known as the Myall Creek Massacre.

There, I walked along the trail which marks the gruesome milestones of this iconic event – the first time in Australia’s history that settlers were tried and hanged for the murder of Aboriginal people.

I took the Aboriginal axe, with our family name impossible to erase from it, and buried it at the site, not only out of respect for the Aboriginal lives lost, but also those in my own scattered family.

Night was falling when I arrived back at the Inverell police station, where a large envelope awaited me. At a motel out of town I pored over its contents, like some terrible play in which my parents were protagonists.

Buried deep in the court transcripts, describing in detail how mum was found guilty of multiple counts of theft, was the news of one shop owner who’d waived all charges in the light of the psychologist’s report, and the one who’d refused.

The sentence in Mulawa Womens’ Prison in Sydney, a day’s drive away from her children, detailed the number of days’ imprisonment resulting from the value of each item of clothing stolen.

The transcripts of friends who stood in the dock spoke of her good character.

The psychologists’ report itself – one clinical, succinct letter linked mum’s behavior to deep feelings of guilt and shame about the death of her third child, the result of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

And then the suspended sentence – no jail time to be served, in exchange for a warrant of good behaviour.

I suddenly understood why mum did not put up a fight for her financial share of the marriage settlement. Buying her freedom had cost our family dearly, and walking away with nothing but a car and some furniture, she might have felt she’d repaid her dues.

I could also see why she eventually left town, allowing the myth to emerge that she’d left dad, not the truth, which was all the other way around. Our family name on ‘Burge Bros.’, an Inverell shopfront, speaks of our pedigree as descendants of proud local shopkeepers, which mum might have felt was brought into disrepute by a depressed city girl. Housed in the same precinct was the shop whose owner would not forgive her.

I remembered how mum recalled being interviewed by the police after my brother died. It was a matter of course, apparently, that the mother was the first subject of investigation after the death of a child who had been laid in his bed by her arms only hours before. Lindy Chamberlain was to face that same moment only seven years later.

And I remembered it was mum who told me about the Myall Creek Massacre. While the other adults were playing tennis at the courts near the creek, she pointed to the hillside and whispered to me about what had occurred. Whispered. Not to the other kids, or any of the white adults enjoying weekend sport, but just to me.

The Myall Creek Massacre memorial was eventually the subject of an Australian Story episode in which descendants of the settlers who committed the crimes reached out in reconciliation to the descendants of the Wirrayaraay people who were slaughtered.

But in its first decade, it endured vandalism. Not brainless destruction, but calculated censorship of the facts about the case and its impact on lives.

It’s a beautiful part of the world, the place I was born, but it can be a harsh place too.

The shock and grief wrought on one family in the wake of the sudden death of one baby tells us how magnified the same emotions would have been after the sudden slaughter of multiple defenceless women, children and old men at Myall Creek, but despite the well-known contributing factors of depression and grief-related kleptomania, there was little reconciliation or understanding on offer for my mother in the 1970s. The community was still coming to terms with what happened to the Wirrayaraay.

Mum got away from Inverell and made a new life. Grandma died in 2008 and we gathered in Inverell for her funeral, but no-one in our family lives there anymore.

I’ll go back to Myall Creek one June for the annual memorial service. Hearing the true story of the place probably marks the start of my journey to being a writer.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.