The fourth in a series of retrospective pop culture reviews revisits the historical romance that reignited the careers of Judy Davis and Hugh Grant…

TWO-THIRDS OF THE way through James Lapine’s 1990 film Impromptu, Mandy Patinkin (as 19th century French poet Alfred de Musset) stretches his face towards the camera in full clown whiteface and viciously shuts down his flaky colleague Hugh Grant (as Polish composer Frédéric Chopin), shouting, “Art never apologises!”

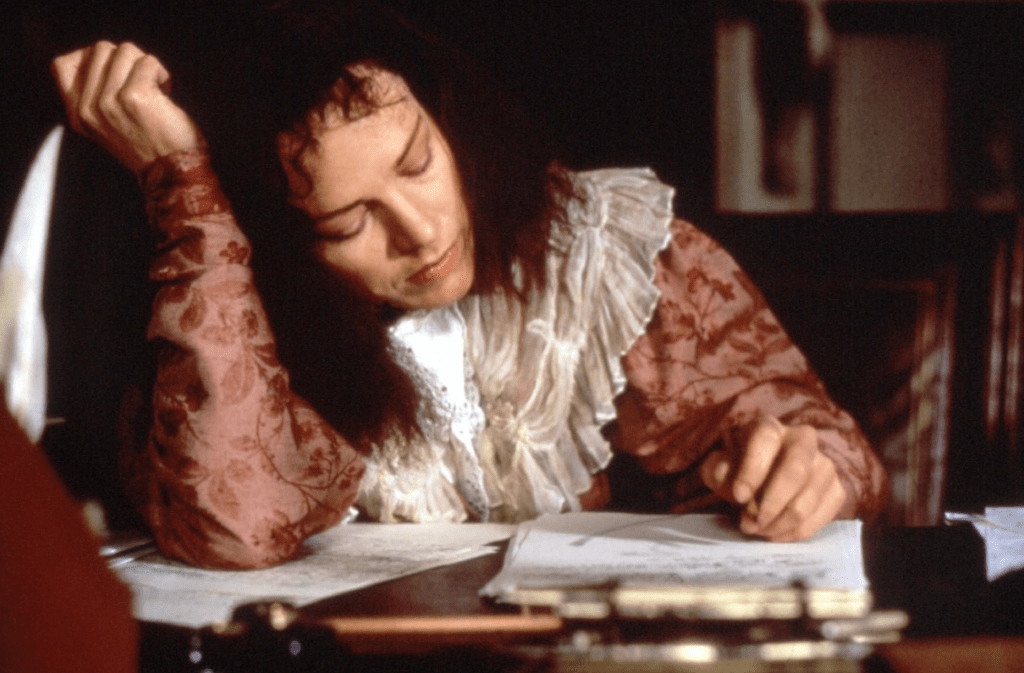

It heralds an explosive turning point in screenwriter Sarah Kernochan’s reimagining of the notorious affair between French writer George Sand (played with pants-wearing, gun-toting, acrobatic gusto by Judy Davis) and sickly Chopin (in the hands of comedically brittle Grant).

Legends of the 19th century’s French Romantic era have joined Sand, Chopin, de Musset, composer Franz Liszt (Julian Sands), writer Marie d’Agoult (Bernadette Peters), and painter Eugène Delacroix (Ralph Brown) at the bucolic retreat of patron Duchess d’Antan (Emma Thompson).

In a black comedy akin to Peter’s Friends meets Dangerous Liaisons, picnics, croquet and illicit sex punctuate Madame Sand’s escapades from former lovers. All the while she simply wants to seduce the man behind the music: the phlegmatic and reclusive Chopin.

He represents a higher form of expression to the brash novelist’s hungry heart. Trapped by a seemingly unconquerable object of desire, the great feminist novelist meets her match, and in the fallout of this summer jaunt Impromptu finds its feet as an original and compelling romance.

Romantic Heroism

The film contains several treats, particularly Thompson’s early comedic turn as the hilarious Duchess d’Antan; and Elizabeth Spriggs as an enthusiastic fan who corners Sand just as Chopin’s music really starts to beguile her.

There was near-universal critical praise for Judy Davis in another career-defining portrayal of a writer at a very different stage of her career to the aspiring Sybylla Melvyn in My Brilliant Career (1979).

“A great actress in a great role,” wrote Terrence Rafferty in The New Yorker. “Davis makes Sand’s passionate absurdities both funny and tremendously moving; this woman’s willingness to embarrass herself seems a kind of romantic heroism.”

Davis stepped up to play the unconventional Sand at a critical time of her career, and put an heroic effort into promoting her first international lead role since A Passage to India, the production that left her with that ‘difficult actress’ reputation.

A 1991 interview with the Los Angeles Times from a Hollywood hotel reads a bit like a charm offensive. Confined to the descriptor of “Australian actress”, Davis delivered several bombshells that can be read as a form of art in a state of apology.

Her up-front explanation to the notorious clash with “autocratic” British director David Lean (“we got into an actual screaming match in India”) came the very month of the movie titan’s death. This is counterpointed with revelations about Impromptu, shot entirely in France with a director who did not speak the language, “a recipe for disaster” dodged due to Lapine’s “staying power”, according to Davis.

Yet despite her picking up an Independent Spirit Award for best actress, in a role that amplified Davis’ independence, Impromptu failed to outsell its modest budget.

Discordant Twits

Some critics focussed on the director’s inexperience. Renowned for his Pulitzer Prize-winning libretto of the Broadway premier of Sunday in the Park With George (complete with Peters and Patinkin in a Sondheim masterpiece exploring France, art and love) Lapine’s film debut came off as lacking in big-screen technique.

“When he introduces the music of Chopin and Liszt into the proceedings, the effect isn’t revelatory, it’s discordant,” wrote Peter Rainer in the Los Angeles Times. “It’s impossible to believe that such sounds could have issued from such twits.”

Yet Rafferty found more nuance in Grant’s performance, a precursor of portrayals to come: “A brilliant caricature of the Romantic ideal of the artist; he gives the character an air of befuddled unworldliness.”

Kernochan might have put one of the Romantic era’s greatest mysteries on the page – exploring why the reticent Chopin succumbed to the steamroller Sand – but Hugh Grant and Judy Davis came into their own portraying it.

Drawing on Sand’s strength, Chopin fronts up to a duel with one of her former lovers. He fails miserably and she picks up the pieces, but left to their own devices in a rural farmhouse (designed with exquisite simplicity by art director Gérard Daoudal) Sand and Chopin are finally able to work themselves free of artifice.

By then, she’s adopted her real name, Aurora, and taken to dresses (Jenny Beavan’s outstanding work). He shrugs off his shyness in a tender and unpredictable bedroom scene where, as it turns out, artists do apologise when they seek true connection.

In the hands of key creatives Lapine and Kernochan – a spousal team in a rare collaboration – Impromptu says much about the meeting of minds that is possible for artistic couples.

Chopin allowed Grant to realise his potential as a leading man who can embrace his pathetic side, and Sand gave Davis the opportunity to transcend her independent reputation by owning it.

Impromptu is streaming on Apple TV.