“You’re a writer, right? Keep it up.”

SO, you’ve completed multiple drafts of your manuscript, you’ve reworked its plot and tweaked its narrative, and it’s been sent to beta readers to see about its readability. You’ve done the work. Excellent. Here’s a list of things to be getting on with while your book is off your desk.

Write another book

Writers are always getting ideas, and the chances of finding inspiration for more books while writing one is very high. Act on that motivation by sifting through ideas for what’s got legs. Now that you have one book being read, maintain your regular writing schedule by getting another manuscript down. You’re a writer, right? Keep it up.

Second book syndrome

Invariably a malady of high-maintenance, traditionally-published authors who find their creative well has run dry with all the attention, ‘second book syndrome’ strikes when writers have too much thinking time and allow their writing schedule to go by the wayside. Instead of indulging in a round of writer’s angst, a good fix is to just start writing again and never allow space for this first-world problem to get a grip. If you’re keeping up with Write, Regardless! you’ll know that a regular writing schedule is a must. What better way to avoid second book syndrome than to have one written by the time you’ve published your first?

How’s your list looking?

No book publisher in the world prepares just one title and focuses all their attention on marketing it. All publishers, large and small, release annual lists of titles. If you are heading for the independent publishing pathway, you’ll need to publish a list. If you plan to persist until a publisher accepts your manuscript, you’ll need more books in the pipeline, in fact their very existence may sway a publisher’s view of your viability. Readers love to be loyal to their favourite authors. When they find you, ensure you have a list of titles on offer.

Get reading

Even better, beta read for another writer, there really is no better way to see how plot and narrative work. When they say that good teachers learn as much as their pupils, this is what they mean: reading another’s manuscript will shine a strong light on your own. Spend some time reading published books. With your new writing knowledge, you’ll probably learn something fresh from an old favourite, or you may notice how the ‘latest, hottest thing’ in the book trade is not all that hot or new: maybe the writer is simply adept at good plotting and narrative, and found original ways of utilising established storytelling techniques. Reading will show you how far your writing has come.

Cards close to your chest, writer!

Cards close to your chest, writer!

The great temptation, in this isolating, internet-driven world, is to tell everyone you’ve finished writing a book and bask in the encouragement your peeps are bound to bestow on you. There is nothing more dangerous for the emergent writer than this kind of public display. It builds an expectation of you and attracts the inevitable question: “So, what’s your book about?”, which you might be prepared for, but will take a chunk of self assurance out of most writers each time it’s asked.

A brainchild is born

There are times and places to share the news of a book’s birth. Join a writer’s group and let everyone know of your completed manuscript (a great way to find beta readers); or tell select friends who respect your creative boundaries (but be very sure they do). If you are planning to independently publish your book, you’ll eventually need to make an announcement to your social media network, but now is just not the time, when you don’t even know for sure what the book will be called. Don’t confuse manuscript completion with the start of a book’s marketing campaign. For now, just keep marketing yourself as a writer in your fields of expertise. Readers will assume you have books in the pipeline.

Extend your networks

By now, you should have a growing social media presence, fed by your regular online articles. During this process, you’ll have naturally seen and read work by other writers, published in other networks. Set aside some time to research and send your work to these websites and social media feeds, particularly if they are linked to your subject matter.

Offer articles for free

“Focus your energies on creating more work and increasing its reach.”

The people behind websites and social media groups (who sometimes identify themselves as editors) will appreciate an approach from a writer offering free content, which is as simple as them sharing your posts. Some feeds will allow you to self post while following a set of group guidelines; others will offer you access as a site author or ‘admin’. Ensure your work is quality journalism and always has a link back to your website or social media assets, which will allow readers to find you, follow you and therefore access your published works down the track. The value of your posts being published is not in charging per word, but in increasing your social media following: your future audience.

Review a book

Preferably an independently published book. Whatever path your writing career takes, the most generous thing you can do as a participant in the publishing industry is to regularly review books. Critical responses are a great way to fill your online publishing schedule with content that reflects on you as a good writer and increases your reach to potential readers. Here are my tips for good reviewing.

Recap

In terms of announcing your book is in a complete form, less is more at this stage, which is the antithesis of the ‘share everything’ world we have made for ourselves; but your work and sense of wellbeing as a writer depend on a bit of containment at this stage. Focus your energies on creating more work and increasing its reach.

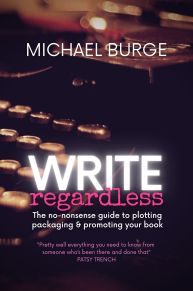

An extract from Write, Regardless!

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.