The first stop in a new series of literary excursions explores how the Queen of Crime created a rural rabbit hole to augment her oeuvre…

NOT FAR FROM genteel St Mary Mead where Miss Marple resides, less than two hours by car from Hercule Poirot’s London pad, is an essential crime readers’ destination that even staunch fans of Agatha Christie have probably forgotten about.

As the name suggests, Market Basing is a typical English market town. The wide central square is the main clue about that, although a slow tractor on any road approaching the place will likely be your first encounter with local farmers.

But Market Basing is no backwater: Christie delved into the district regularly throughout her oeuvre.

Poirot and his sidekicks Captain Hastings and Inspector Japp took a short break there in the 1920s; and Poirot and Hastings returned in the 1930s. Superintendent Battle worked a case linked to the town in 1929. Miss Marple probably never went, but she did know of a bus conductor who serviced the St Mary Mead to Market Basing service in the 1950s; and amateur spy duo Tommy and Tuppence Beresford got embroiled in a scandal there a decade later.

With its growing outer-urban population, the town has a general hospital (which features in Crooked House, 1949). There’s a police command (called upon in The Secret of Chimneys, 1925); a thriving high street (which inspired a shopping trip in The Seven Dials Mystery, 1929), and Hellingforth Film Studios (a key location in The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side, 1962) is just six miles away.

But the town’s perennial industry is real estate, and the streets are replete with busy agents offering desirable farms, manor houses for rent or purchase, and large tracts of land.

Some reckon Market Basing is Christie’s stand-in for Basingstoke in Hampshire, or an homage to her final home in the Oxfordshire village of Wallingford; but true fans know full well the township is actually in the county of Melfordshire, and if you don’t know where that is you have some reading to do.

Nobody Knows Us

Start with Christie’s 1923 short story The Market Basing Mystery (published in Poirot’s Early Cases, 1974) in which Poirot, Hastings and Japp take a weekend away from the London rat race.

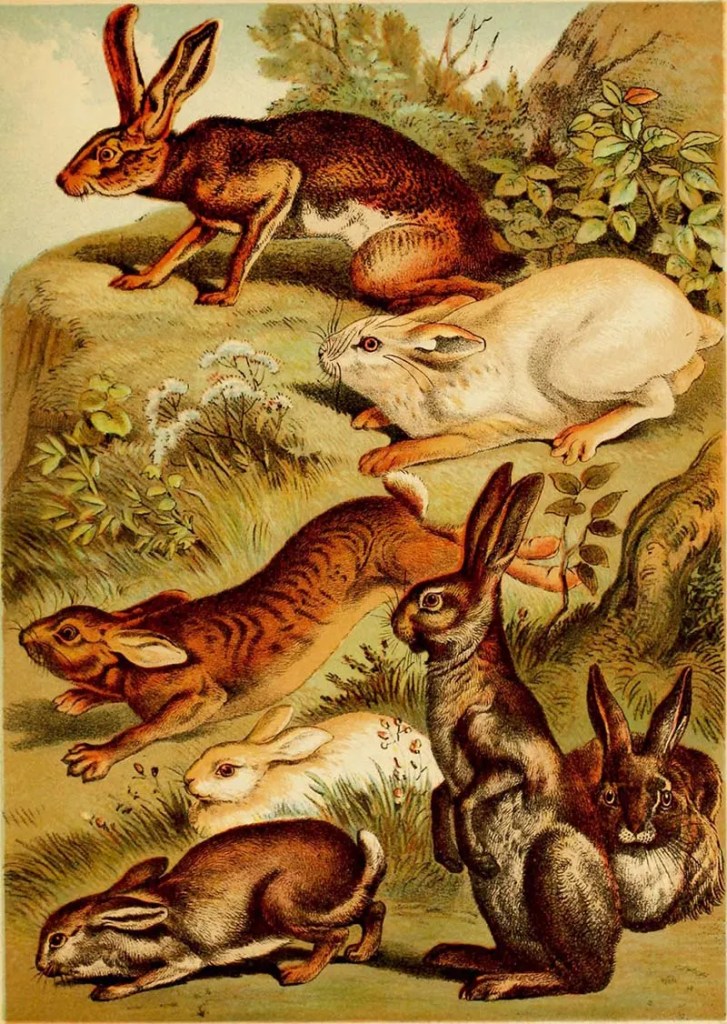

The story opens with a hearty pub breakfast while Japp celebrates the benefits of a gents’ country break in a place where, “Nobody knows us and we know nobody,” he says. Hastings is narrator and he makes deft observations about men, appetites and rabbits before the renowned sleuths are called on to investigate a local locked-room mystery.

Most of the action in Dumb Witness (1937) takes place in Market Basing after local spinster Emily Arundell writes to Poirot, apparently after her death. The Belgian detective recruits Colonel Hastings to drive him out to the town on the scent of a clever poisoner Poirot refers to as a rabbit.

A generation after World War Two, the progress of Market Basing can be observed by joining Tommy and Tuppence Beresford in By the Pricking of My Thumbs (1968), an intriguing chase that begins in a nursing home and leads back to Market Basing, flushing out several hares responsible for missing women, jewel heists and derelict houses.

It’s here, in the last decade of Christie’s life, that she may have left clues about a rather brazen rabbit hole at the core of English country life.

Ending Nowhere

Analysis of Christie’s massive literary output often draws accusations of lacklustre storytelling. Crime author Robert Barnard’s review of By the Pricking of My Thumbs is one example:

“Half-realised plots and a plethora of those conversations, all too familiar in late Christie, which meander on through irrelevancies, repetitions and inconsequentialities to end nowhere (as if she had sat at the feet of Samuel Beckett).”

I suspect Barnard missed the point of a novel that employs meandering, memory loss and ageing as major themes; but love or loath her work, Christie was a shrewd observer of English society and documented what she perceived as its decline in the late 20th century.

She was careful to add a new county name – Melfordshire – for the setting of By the Pricking of My Thumbs, considering the changes she witnessed under the Local Government Commission in the mid-1960s; and the threat of a dormitory town being built on major landholdings in the Market Basing district in that novel.

But the Queen of Crime could be accused of a major plot hole in her collected works when she gives Poirot and Hastings absolutely no recollection of their 1923 weekend in Market Basing when they revisit the place in 1937.

Did Dame Agatha simply forget her earlier work, or are we supposed to take this crime fiction author as she presents herself, alleged ‘errors’ and all?

Rather deliciously, if we do take her at her word, Market Basing becomes even more sinister than it first appears.

Awful Things

Let’s start with a fact: Hercule Poirot rarely, if ever, forgets.

Since neither he nor Hastings refer to their 1923 weekend in Market Basing while revisiting the town twice during 1937 in Dumb Witness, they must be avoiding the memories for a reason.

Could it be embarrassment, an “I won’t mention it if you don’t” pact? Clues lie in Hastings’s 1923 pub brekky musings from a Belle Époque poem with suggestions of depravity.

“That rabbit has a pleasant face,

His private life is a disgrace.

I really could not tell to you

The awful things that rabbits do.”

At first glance, Hastings, upstanding gentleman that he is, appears to be comparing Market Basing’s residents to randy, big-eared, four-legged herbivores. But the depravities he euphemistically refers could be those of the men around the table.

Read the opening page of The Market Basing Mystery through this lens and the hearty breakfast devoured after a night in a town where “nobody knows us” has the vibe of the morning after a boys’ night out.

None of the men reacts to Hastings’s rabbit reference. Japp actually changes the subject back to the food. The trip was all his idea because he’s “an ardent botanist” able to reel off the botanical names of “minute flowers”.

But what if Japp’s botany is a way for a Scotland Yard gumshoe to describe his weekend predilection for plucking specimens of the two-legged variety?

If so, it’s hardly a surprise that Poirot and Hastings never again mentioned their lost weekend in Market Basing.

Specimens in the Hedgerows

Four decades on from this short story, Christie returns to the botany of Market Basing in By the Pricking of My Thumbs when Tuppence Beresford meets the vicar of Sutton Chancellor (a village in the parish) who is searching for a lost headstone in the churchyard in 1968.

At that stage, the novel is shaping up to be a beguiling, sinister tale with references to clandestine outdoor trysts, pretty young women visiting strangely empty houses and “getting into trouble”, and a serial killer who attacks girls in the woods.

So when Tuppence asks about one particular house, just like Japp in 1923 the vicar changes the subject: “… you can find quite rare specimens. Botanical, I mean,” he says.

Tuppence refuses to be fobbed off by botany, but all the talk of flowers in the hedgerows along the lonely roads around Market Basing in the 1960s might be coded language from a devout man warning Tuppence of local “goings on”.

Masterful Illusion

Rabbits and hares, flowers and hedgerows… if it all sounds like a mare’s nest, that’s because it’s supposed to.

Read Christie’s three major Market Basing stories in sequence and you’ll see the masterful illusion she wove around this district. There are no spoilers to be had (Christie took great care in that regard), but you’ll be one step ahead of Tuppence Beresford in the 1960s throughout By the Pricking of My Thumbs when you’ve had a taste of the town’s depravity from the 1920s in The Market Basing Mystery.

It’s now over half a century since Market Basing last cropped up in crime fiction. Since then it’s no doubt been absorbed into another county, the hedgerows have been bulldozed, and several dormitory towns raised and renovated many times over.

But you can still enjoy the botanical ‘specimens’ and ‘wildlife’, now you know what you’re looking for.

Main image: A Hare in the Forest, Hans Hoffmann, c.1585 (Getty Museum)