The second in a series of retrospective pop culture reviews examines the late actor’s overlooked triumph as an Irish spinster caught up in a crisis of faith…

WHEN A COMMUNION wafer gives genteel young Judith Hearne (Emma Jane Lavin) the hiccoughs and other girls in the congregation start giggling, a painful demonstration of Catholic self control is delivered by a pious aunt played by the formidable Wendy Hiller.

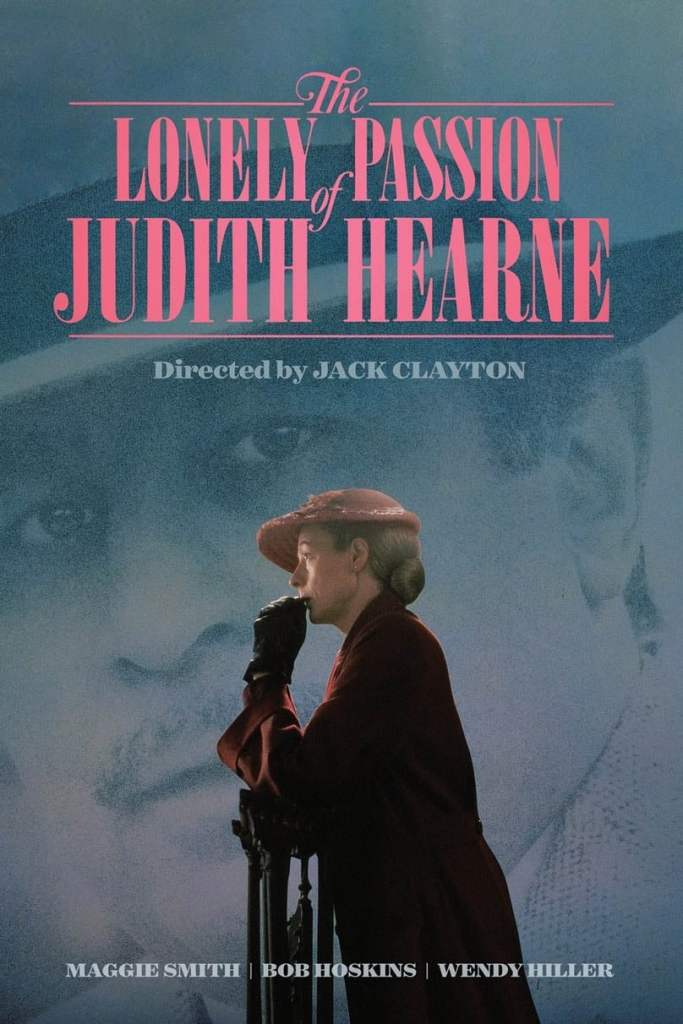

It’s the opening scene of The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1987), and young Judith’s stoic face fades to that of middle-aged Maggie Smith (1934-2024) as she’s delivered to the door of a devout 1950s Dublin boarding house.

Now so down-at-heel that she ascends to her latest shoddy digs with the resignation of a martyr, the question of why nothing appears to have changed for Judith in the intervening decades is masterfully explored in the big-screen swan song of British director Jack Clayton (1921-1995) .

Yet despite Smith winning the BAFTA for Best Actress, the role of hapless part-time piano tutor Judith Hearne was commonly overlooked in her obituaries, basically because hardly anyone got a chance to see it.

After portraying a series of upright matrons in the 1980s (most successfully as Charlotte Bartlett in Merchant Ivory’s A Room With a View), Judith Hearne offered Smith another “prime” akin to the global attention she garnered as Jean Brodie.

Miss Hearne exhibits all Miss Brodie’s blind passion, but where the schoolteacher used bravado to stave off scandal in a conservative society, the piano teacher is shamed into silence; and this exquisite production from the Handmade Films’ stable was similarly humiliated at the box office.

There had been warning signs. The source material – Brian Moore’s 1955 debut novel – was banned in the Republic of Ireland as anti-religious, and notorious for its unsatisfactory ending. Director John Huston optioned the material in the 1960s but failed to mount a production, even with Katharine Hepburn onboard as Judith. During Clayton’s shoot, no Irish church would permit a location crew into their altar to recreate the protagonist’s crisis of faith.

Yet this lapsed-Catholic director and his screenwriter Peter Nelson saw great potential in the story’s quite ordinary setting. We wince with Miss Hearne as she nervously pokes her way into the breakfast room, but we cringe when she’s instantly attracted to fellow boarder James Madden (Bob Hoskins, a dose of American vigour in austere postwar Dublin).

Once Miss Hearne’s delusion takes hold – that Madden’s hints about a business partnership are a reciprocation of her romantic availability – we want to look away.

But we cannot, especially once deadly sins start to boil up. Madden’s sister, the landlady (played with deviously good manners by Marie Kean) and her corpulent dilettante son, Bernie (pitch-perfect Ian McNeice) conspire to ruin Judy’s dreams by exposing the penniless truth about James.

Achingly, he can’t help but see money in Miss Hearne’s heirloom jewels as she prays at mass; an occasion she construes as a first date ahead of a brand new life as a hotelier’s wife.

Augmented by Georges Delerue’s heartbreaking score and a supporting cast that includes Prunella Scales as Judith’s indifferent school friend, this powder keg burns inevitably towards the exposure of the heroine’s real passion, and the unforgivable expression of Madden’s lust.

All in the wrists

Caught up in a financial dispute between producer Handmade Films and distributor Cannon, Clayton’s passion project had a limited US release in late 1987 before being shelved. Despite awards attention for Smith and Hoskins in 1988, the film disappeared into the wallpaper, much like its heroine.

Reviews were polarised. Janet Maslin described Smith as “almost too good” in the role, because her subtlety only highlighted the production’s “obviousness”. Yet Pauline Kael called the film “a phenomenal piece” and recognised Smith’s pioneering task: “There has probably never been another movie in which a woman rejected the Church fathers’ ready-made answers.”

Long known for the ‘wrist acting’ that she admitted in a 2018 documentary was appropriated from her longtime friend, actor Kenneth Williams, Smith puts her fine joints to expert use when charting Judith Hearne’s inescapable weakness – her alcoholism.

Like voyeurs, we get a glimpse of how far Judith is likely to fall when Smith has her impersonating Hedy Lamarr, all hips, elbows and chin as she poses sensually on her bed after returning from what she believes was her second date with Madden.

This is the comfortable comic schtick of Smith’s matrons, yet something else emerges once the booze flows and Judith’s religious conflict bursts like a shockwave.

Her wrists aimed upwards like a drowning woman, Miss Hearne appeals for help from a priest. But when it’s apparent that he’s as doubting as she is, Smith has Judith slam a suddenly powerful, un-bent forearm into the stone font as though daring the holy water to cleanse her lack of faith.

Unsatisfied, she aims both wrists at the tabernacle and attempts to claw her way into grace.

After taking her passion right up to her god, it’s arguable whether Miss Hearne ever reconciles her addiction within the patriarchy she so powerfully bucks. Wrists ultimately manacled by nothing more than dressing gown pockets in the convent asylum for her last ‘date’ with Madden, Maggie Smith appears to recognise Judith’s ultimate surrender as a feminist triumph of self forgiveness, just for today.

Witnessing her inhabit that discovery – when Moore, Nelson and Clayton all seemed to overlook it – Smith’s work here is much more that “almost too good”. It’s unmissable.

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne is streaming on Amazon.