The second stop in a series of literary excursions examines how one of the world oldest cave systems inspired a crime novel…

THE WAY TO Jenolan Caves within the Blue Mountains National Park of New South Wales has always been long and winding. The Burra Burra clan group of the Gundungurra nation, the region’s Indigenous custodians, tell a Dreamtime story of ancient spirits journeying there via the waterways and valleys. European settlers descended the steep ridges on foot and horseback from the 1830s, and visitors have traversed a variety of precarious access roads ever since.

The approach gives you plenty of time to cast off the everyday world. As a casual tour guide between 2008 and 2012, I used the inspiring commute to ponder the extensive stories of the place.

Like many trainees before me, I’d gleaned the local tales from my more experienced peers. It didn’t take long to realise that the job had granted me rare access to a unique oral history, although my journalistic experience told me it was a paradoxically flawed mish-mash based on limited primary evidence.

Almost instantly I felt there was a novel in this massive well of storytelling, and to find it I eventually decided to cut through Jenolan’s tourist tales to recreate a time when the caves sat on the edge of the colonial frontier. A place that settlers viewed with suspicion, not wonder, very often through a lens of faith.

What drove me were the stories few wanted to talk about, particularly First Nations peoples’ connection to the region; the cattle farmers who gradually occupied the same countryside; the Wesleyan Methodist community of the nearby region once known as Fish River Creek, now Oberon, and the role of women in early cave exploration.

Crime was never far from the colonial experience. The massacres and random killings of Aboriginal people and reprisals against settlers are now referred to as the Frontier Wars. The occupation of the land was not possible without the importation of convicts to build roads and towns, a mounted police force to impose British law, and Christian missionaries to uphold ethical standards.

Long before I embarked on a first draft, I interviewed Gundungurra elder Aunty Sharyn Halls at Echo Point in Katoomba, listening to her share knowledge about the pathways and waterways used by her ancestors between the Oberon region and the Southern Highlands. It helped me to understand how different the approaches to the caves were in the 19th century, and that new perspective encouraged me to question everything we think we know about Jenolan.

Errors and Conundrums

Jenolan’s oral tradition tells stories of two early female explorers. The more recent was Catherine (‘Katie’) Webb (1861-1941), daughter of a local businessman and visitor to Jenolan in its Victorian heyday.

Katie’s 1881 discovery of the chamber that bears her name in the Chifley Cave took place at a time when women were regularly photographed in caving attire. But another woman whose exploration pre-dated Katie’s by two decades hangs barely visible in the Stygian gloom.

I first heard about Jane Falls while on a training tour of the Lucas Cave. She sometimes rates a mention when Jenolan guides interpret the soaring Cathedral Chamber into which the first European explorers stumbled in January 1860. Some will tell you she assisted in that expedition, while others credit her with the discovery at an earlier date.

A person known as ‘J. Falls’ was mentioned in the letter written by George Whiting to the Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal about that expedition. This could be Irish emigrant and Oberon resident Jane Falls (1829-1911), or her mother Jane Falls née Nelson (1802-1893). It could also be Jane’s brother James Falls (1834-1911) or his twin George Falls (1834-1867) recorded with the wrong initial, because when it comes to giving credit for cave discoveries, Jenolan is full of errors and conundrums.

The use of initials instead of full names was common on hand-engraved memorials and in newspaper typesetting. Catherine ‘Katie’ Webb’s 1881 discovery resulted in her name being inscribed on an early plaque (now long gone) as ‘C. Webb’ in a list of ‘before-mentioned gentlemen’, her sister sister Selena among them, recorded as ‘S. Webb.’

But in 1995, according to what became known as the Historical Inscriptions Project (kept by Jenolan Caves Historical And Preservation Society), a full hand-written signature of Jane Falls was discovered in Jenolan’s Elder Cave, dated February 27, 1854. It’s a long way from the Cathedral Chamber in the Lucas Cave, but it’s one of the earliest names inscribed in the entire Jenolan system.

The obvious way to clear up the matter is to fact-check George Whiting’s claim that he and fellow explorer Nicholas Irwin were the first to enter the Lucas Cave. That’s problematic, because when an official plaque about cave discoverers was dedicated in the Grand Arch in the 1920s, neither man got a mention.

Photographs of this event reveal a well-attended ceremony on February 23, 1929. A clock on the rock wall pinpoints the solemn moment, just after three in the afternoon, when first in the line of dignitaries gazing up at the plaque was eminent explorer and geologist Sir Edgeworth David.

The plaque credits N. Wilson, G. Whalan and G. Falls with the co-discovery of the Lucas Cave in 1858, and is still pondered over by cave visitors today. But its veracity was challenged in the NSW papers for a few years after its dedication, and six decades later someone who knew Jenolan better than most made a judgment about it.

In his paper and subsequent book The Men of Jenolan Caves 1838-1964 (1987) speleologist and former Jenolan guide Basil Ralston was quick to reject the plaque in favour of George Whiting’s 1860 letter to the editor.

Whiting’s letter is nothing if not detailed. It reads like he was discrediting another claim when he described he and Nicholas Irwin finding the way in a “… pristine state, unbroken and undilapidated; not the slightest trace or vestige of human being ever having set foot there.”

But that was never the only doorway into the mountain.

Suspended between contradictory oral histories, citizen journalism and widespread speculation, the story of exactly who discovered Jenolan’s Lucas Cave sometime in the late 1850s remains an open case. Jane Falls’ role most certainly cannot be ruled out, but if she was involved, many more questions hang in the air.

Small Obfuscations

Further research on Whiting and Irwin only makes things murkier.

The George Whiting who wrote to the papers about his 1860 exploration party is extremely elusive in the records. Some of what we think we know about him comes from a letter that historian Ward Llewellyn Havard wrote to the The Sydney Morning Herald in 1934, with an aside describing Whiting as “tutor to Charles Whalan’s children”.

Early Oberon settlers Charles Whalan (1811-1885) and his brother James (1806–1854) happened across the caves in the 1830s. Elizabeth Whalan (1810-1899), married to Charles in 1836, was said to be the first white woman in the region.

The couple’s homestead Glyndwr became a popular base for expeditions to visit the underworld. They had many children and there are a few colonial-era George Whitings who could have educated them.

The closest candidate is George Robert Whiting (1834-1922), whose obituary locates the Oxford-born settler on the Turon River during the Gold Rush of the 1850s, not far from the Whalan family at Oberon. His later role as a teacher at Sydney’s ‘ragged school’ for destitute children suggests he had tutoring experience.

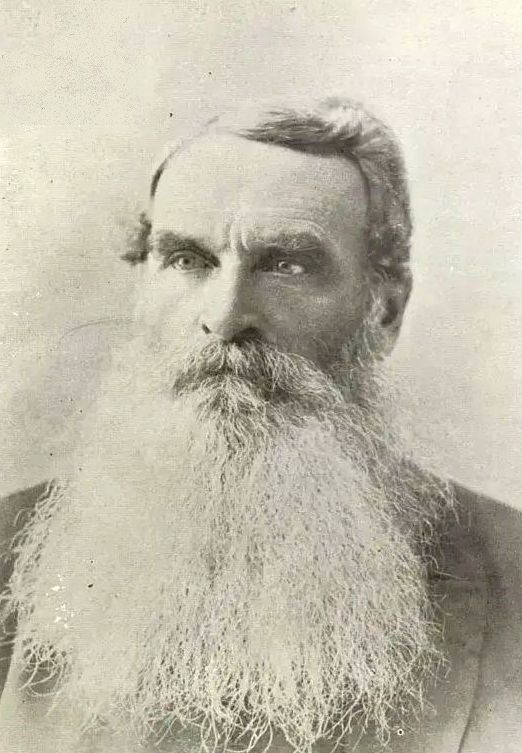

Explorer Nicholas Irwin is even sketchier because his name began to get mis-spelled at an indeterminate time, possibly in George Whiting’s 1860 letter that describes “Irwin” as “an old experienced guide”. Yet Charles Whalan’s son Alfred wrote to the Lithgow Mercury in 1899 describing the same man as “Urwin” and calling him Whalan’s “servant” who accompanied his master to the caves on an exploration in the early 1840s.

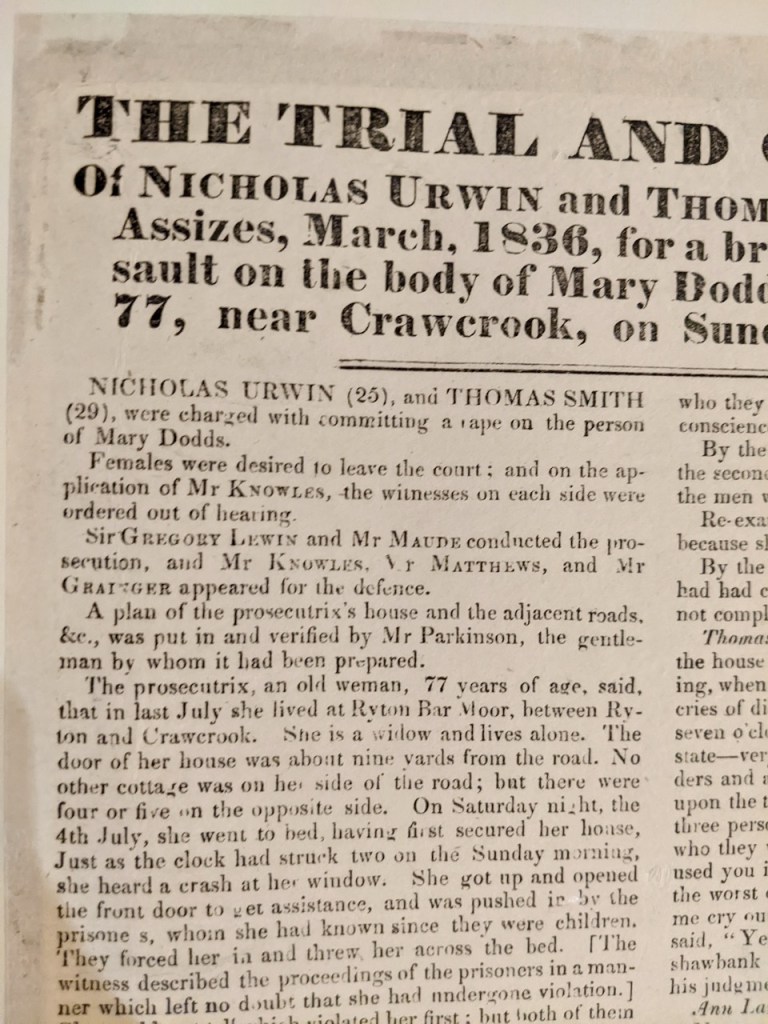

Nicholas Urwin (1808-1899) was in fact a former convict sentenced to hard labour in the burgeoning colony, but he was no petty thief. He was a lifer, transported to NSW after avoiding the noose. His crime: the rape of Mary Dodds, aged 77, in Country Durham in 1835.

Little wonder that his name never ended up on any plaque at Jenolan.

Yet after being granted a ticket of leave in 1845 and a conditional pardon in 1853, Urwin could be said to have attained something of an unconditional pardon in 1870 when Annie Mary Wild agreed to marry him. They produced twelve children prior to his death at Peelwood, aged over 90.

There can be no doubt the Whalans knew of Urwin’s crime. A convict’s record stayed with them through each transition towards their freedom. We know more about convicts than we ever could about many free settlers, simply because a description of their appearance may have been required had they escaped or reoffended, something it appears Nicholas Urwin never did.

George Whiting might have altered the spelling of Urwin’s name to Irwin as a means of disguising a known sex offender in much the same way as a convict could be construed as a “servant”; or a female explorer concealed by recording her initial only. Once again, small obfuscations resulted in huge ramifications for Jenolan’s view of itself and its history.

Female Gaze

Jane Falls’s story probably got a bit lost in Jenolan’s oral tradition for the most obvious of reasons: According to obituaries, she lived in the Oberon district from the 1850s until her death in 1911, but for the bulk of that time she went by her married name Jane Eaton.

After her husband William’s death in 1874, she emerged in reports about her wool and hops growing operations, and while her mother Jane was eulogised as fervently devout in 1893, Jane Eaton was remembered in 1911 as ‘well respected’ without any religious fanfare. Her grave remains unmarked in Oberon’s Old Methodist Cemetery and her progeny occupied the region for another century.

Unlike the stories of Katie Webb there is little detail, however mythical, about the cave explorations of Jane Falls. Faced with recreating what she might have achieved, I was left to imagination.

A dose of allegory allowed my early drafts to take shape. I was inspired by the classical Greek legend of Eros and Psyche. E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India was another influence, and I took a leaf out of a powerful modern Australian myth: Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Psyche is sent to the Underworld; Lindsay’s schoolgirls disappear into a monolith, and Forster’s Adela Quested confronts her hypocrisy in a cave. But just as interesting is what happens above ground, when half-truths take flight.

While mentions in a few newspaper reports and signatures on cave walls give scant evidence for a larger tale about Jane Falls, accepting the limitations freed me to explore what it would take for an unmarried, female, Irish émigré living in a devout Methodist community to participate in the discovery of an Australian cave in the mid-Victorian period; and why she would leave so few traces of her achievements.

If the rather abstract figures of George Whiting and Nicholas Irwin warrant a place in the interpretation of Jenolan Caves, then so too do Jane Falls, Katie Webb, and the generations of women who hosted its visitors, from Elizabeth Whalan and Lucinda Wilson to Barbara Chisholm of Caves House. Writers such as Margaret Isabella Stevenson and Agatha Christie also recorded their cave tours in detail and give a female gaze to Jenolan that is often lacking.

Border land of Error

The Methodism running through Jenolan’s settler history led me to research the teachings and principals of cleric John Wesley (1703-1791).

James Colwell’s Illustrated History of Methodism in Australia (1904) outlines the mission to assist the Aboriginal population of Bathurst, which was declining in the wake of the Bathurst War fought in 1824 between the Indigenous Wiradjuri nation and the British militia. It also paints a troubled picture of the Bathurst and Fish River Methodist circuits between 1849 and 1852.

The Reverend John Pemell reported, “the Circuit was low in piety, for there had been a fourth year’s appointment against which the people protested. Great discord existed,” and detailed the abandonment of congregations as a result of the NSW Gold Rush.

Methodist support for Aboriginal people eventually became less of a priority than the survival of diminishing congregations. Many historians describe the broader Methodist mission to support Indigenous people as a failure.

Yet early European settlers thrived on it, and Philippa Gemmell-Smith in her 2004 Thematic History of Oberon Shire directed me to Pemell’s mention about the construction of a sod-walled chapel at Jenolan Caves in 1851.

This apparently pre-dates other buildings at the caves. If it had been raised in the Jenolan valley this soil-constructed chapel was likely washed away by floods years ago. Its disappearance speaks to the broader vanishment of 19th century circuit riders who engaged in “field preaching” and tent revivals, which seemed more of a tradition on the American frontier.

But not so. Up at old Oberon when it was known as Fish River Creek, the Wesleyan circuit saw revivals, conversions and chapel-raising. According to a preacher who knew him, Charles Whalan experienced a conversion to the Methodist faith on the banks of the Saltwater Creek near Glyndwr on his return from a revival at Bathurst in around 1842.

“He was something of a mystic, too. The look into eternity made spiritual things real to him. He had those revelations of the unseen, which only come to those who live in close touch with God. He had dreams and visions, and suggestions which he had no doubt came from God for his guidance; and sometimes perhaps the workings of an active imagination influenced by strong feeling or unconscious bias may have been mistaken for the Divine Voice. There is a border land of error that lies close to the truth, and the step over is taken easily enough and without conscious default.”

This portrait of Charles Whalan by Reverend Matthew Maddern appeared in a comprehensive biography of Whalan in The Methodist in July, 1911, foregrounding Whalan’s work for the Wesleyan faith and leaving his connection to Jenolan as an afterthought.

Tent revivals were common in frontier communities throughout the 19th century, and visiting American preachers were not uncommon during the Gold Rush. Evangelical missionary William ‘California’ Taylor (1821-1902) hosted revivals throughout regional Australia in the 1860s.

Many Irish Methodists practiced being “slain in the spirit” or falling prostrate in ecstasy during preaching. Wesley himself encountered this form of rapture in his travels, as stated in his journal entry of July 14, 1759:

“In the afternoon, Mr B was constrained, by the multitude of people, to come out of the church, and preach in his own close. Some of those who were here pricked to the heart, were affected in an astonishing manner… One woman tore up the ground with her hands, filling them with dust and with the hard trodden grass, on which I saw her lie, with her hands clinched, as one dead, when the multitude dispersed. Another roared and screamed in a more dreadful agony than ever I heard before… I saw one who lay two or three hours in the open air, and being then carried into the house, continued insensible another hour, as if actually dead. The first sign of life she showed was a rapture of praise intermixed with a small joyous laughter.”

If it seems outlandish to equate such phenomena with Jenolan, consider that Havard also wrote about a young stockman, Luke White, who claimed to have seen the Devil parking his horse-driven coach inside a cavern at Jenolan Caves in the 1830s.

White was a convict transported to NSW for seven years before his release in 1834, after which he took up work with various cattle farmers in the Oberon region, including a stint as an employee of Charles Whalan’s. By 1840, he was before the courts again, charged with cattle theft.

Whalan appeared as a witness, although his association with White dealt him a counter accusation of cattle thievery too, for which he was committed and bailed at the time of giving evidence at White’s trial.

White was found guilty and transported to Norfolk Island, but Whalan found god. His biographer Maddern described this as “the great change” of Whalan’s life, after being “more than careless about the concerns of his soul.”

Maddern was very understanding about his old friend Whalan when he eloquently skated around the man’s mystical beliefs, outlining how his “active imagination” traversed a “border land of error”.

There are perhaps no better terms to define Jenolan Caves as a tourism experience and a subject to research and write about.

Look no deeper than the enduring reminder of White’s hellish vision, remembered to the present day in the name of Jenolan’s enormous daylight cavern: The Devil’s Coach House.

Connecting Dots

My literary journey to Jenolan was enriched by listening to Aunty Sharyn, who gave new perspective to my many years of research about the history of Aboriginal life in the region.

As the manuscript came together, Gundungurra traditional owner Kazan Brown assisted me in depicting Burra Burra history, place and cultural practice. I also relied on aspects of Burra Burra culture at Jenolan Caves that have been shared by the Gundungurra Tribal Council.

My experience of guiding groups along thousands of steps inside the caves was a constant inspiration, considering how the winding caverns bind everyone who enters into a common experience, often filled with wonder yet tinged with anxiety.

The underground settings in my book are based on real caverns, although I have engaged a bit of dramatic license in depicting some of the chambers, and how far the characters reach into the mountain and by which means, considering the novel is set in the early 1850s.

But what can we ever really know with absolute accuracy in Jenolan’s “border land of error” when so many tales have been told and tracks covered?

To connect the dots left by history, I re-imagined a fiction of all these lives.

Readers sleuthing after facts will hopefully set themselves free to enjoy my speculation about Jenolan’s discordant year of 1852, and the way the place baffled European settlers who stumbled into the dark, heads full of powerful scripture.

Main image: Souls on the Banks of the Acheron, Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl, 1898 (The Belvedere)