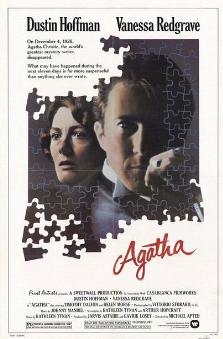

The third in a series of retrospective pop culture reviews revisits the mystery movie that Christie fans love to hate-watch …

THERE’S AN EVOCATIVE scene in the big-screen adaptation of Kathleen Tynan’s novel Agatha when Vanessa Redgrave as Agatha Christie and Helen Morse as her new bestie Evelyn Crawley, languish in a steam room at Harrogate’s Royal Baths in 1926.

In this tranquil, white-tiled, female-only space, the conversation between two fictitious women (Agatha is at that point pretending to be Teresa Neele of Capetown, South Africa; Evelyn is an entirely made-up character) drifts from ageing to the changeability of men.

Evelyn confesses to being very choosy with her lovers, a concept that Teresa is slightly shocked about and attempts to counter with a rather limp argument for faithfulness.

“It hardly seems worth it,” Evelyn replies. “That’s why choosing’s important. We can’t just let things happen to us.”

Up to this point in the film, director Michael Apted (1941-2021) and story writer Kathleen Tynan (1937-1995) had played reasonably fair with the facts, exploring significant gaps between the dots about the infamous disappearance of Agatha Christie (1890-1976).

Her disintegrating marriage, her car crash in Surrey followed by a night train to Yorkshire’s spa town Harrogate, her adoption of a new persona: these are all known facts.

The rest of Agatha (1979) could only be described as a masterclass in how to get away with portrayals of real-life people, or a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when you try.

Unarguably, the time was right. The ‘Queen of Crime’ had died in early 1976 when her cult was at its peak. Her posthumously released autobiography made no mention of her disappearance, but Tynan’s book Agatha: The Agatha Christie Mystery (1978), with its pitch of “an imaginary solution to an authentic mystery”, captured the interest of American and British film producers.

Agatha’s exposition beautifully portrays a collapsing marriage in the home counties between the wars. Timothy Dalton drives the scenes as the well-mannered but hardline Archie, the jaded husband who ignites the hidden survival instinct in Redgrave’s crumbling Agatha.

But American Gumshoe Wally Stanton (Dustin Hoffman in full flight) sniffs out a story in the ruins of the marriage, and as the tension rises, Timothy West’s pragmatic police detective delivers the cynicism that underpins the massive manhunt for the crime writer when she goes missing.

By the midpoint, Historic Harrogate serves up all the flavour of the Roaring Twenties, a decade that had been recaptured so exquisitely and profitably on film throughout the Seventies.

Tynan’s vision for Agatha was bold, yet her book and the subsequent film have been largely forgotten, something only devoted Christie fans love to hate-watch.

Woman in Crisis

Film critic Vincent Canby of The New York Times made allowances for Agatha “given the few verifiable facts of the case”.

“The result is a handsome, rudder-less sort of movie that isn’t quite a mystery story, not quite a love story and certainly not a biography,” he wrote, concluding that the production felt “unfinished”, “aimless” and “pleasantly endurable”.

Pauline Kael of The New Yorker saw “the oddness of genius” in Redgrave’s portrayal, but believed the production team, “haven’t come up with enough for their sorrowful, swanlike lady to do.”

It wasn’t until 2020, in a broad-ranging article Re-writing the Past, Autobiography and Celebrity in Agatha by academic Sarah Street, that we got a thorough examination of what happened to Tynan’s story when it was committed to film.

Street concluded that Tynan’s adaptation of her own novel had a “sympathetic premise” towards Agatha Christie, but unearthed a movie production she described as “torturous”.

“Apart from exploiting intense public interest in Christie, the film involved conflict between other celebrities and professionals who in their different ways struggled to make sense of this puzzling event in Christie’s life,” Street wrote.

Given access to transatlantic film production archives, she was able to examine correspondence between key creatives, tussling over the narrative.

In a 1977 letter to Apted during hurried, late-stage rewrites, Tynan described the characters of Evelyn and Wally as catalysts for the personal growth of Agatha Christie, a “woman in crisis”.

In recent years, much has been written about the mental health struggles of Agatha Christie in the 1920s. But in the 1970s, Kathleen Tynan was one of the first writers to suggest the author’s flight to Harrogate played out a desire for reinvention.

Evelyn Crawley was the emotional guide Tynan gave her, through a reckoning that had been intended to play out in the hands of women.

The original casting for this glamorous, independent character also became apparent in the details unearthed by Street: Julie Christie, who pulled out of the film due to illness. Helen Morse deftly stepped in, but late screenplay rewrites supplanted Evelyn with Wally in the film’s second half. The gumshoe becomes the wayward crime writer’s love interest, something Tynan never intended, according to her archived correspondence.

The major consequence was the unravelling of the feminist thread in Agatha. There’s a trace of it in that steam room conversation, when Evelyn encourages Agatha about not letting things just happen to her. Like a moment of insight in a fever dream, it feels as close to the emotional truth as anything.

Hang onto it when you watch this problematic but gripping film, to make sense of what Agatha does next.

Agatha is streaming on Apple TV and Prime.