A Writer’s review of Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother.

FRESH from witnessing the fuss Lionel Shriver inspired at the 2016 Brisbane Writers Festival, defending the right to use her imagination without being labelled a cultural appropriator, I took to this book with a half-baked plan to test out both sides of the argument.

“Hopeful, insane, self-fulfilling learning curve.”

That failed at the first hurdle, simply because Shriver’s prose is always so darned good it lifts readers high enough off the earth to forget ourselves; but since finishing Big Brother, with its infamous much spoiler-alerted conclusion, it’s easy to see Shriver’s imagination was not heavily taxed in this novel.

It’s a simple set-up: Edison Appaloosa is a failed jazz pianist who comes to stay in Iowa with his successful younger sibling Pandora. She’s turned her back on a catering business but had plenty of luck with her own start-up.

Last time she saw her brother, Edison was every inch the suave New Yorker, and Pandora anticipates being in his slightly louche orbit again; but the monster who appears at the airport is a man she fails to recognise, literally and emotionally, because the inches have piled onto his waistline.

Last time she saw her brother, Edison was every inch the suave New Yorker, and Pandora anticipates being in his slightly louche orbit again; but the monster who appears at the airport is a man she fails to recognise, literally and emotionally, because the inches have piled onto his waistline.

Huge and hyper-sensitive, Edison is hiding the truth beneath the body fat, and his bluster is a challenge to Pandora and her husband Fletcher, nattily portrayed as a calorie-counting fitness junkie. It doesn’t take long for ultimatums to be issued that drive the drama to unexpected places.

Applying some of the plainest fiction I’ve read in a very long time, in Big Brother, Shriver calls to mind her journalism as much as she does any of her novels, lending realism to what might have been a far more clichéd set of characters.

It comes as no surprise that her experience of a chronically overweight brother Greg ‘fed’ both the need to write Big Brother and ‘flesh it out’ with many believable threads that leave the reader in no doubt the author witnessed morbid obesity up close, and shared its impact.

We are ‘stuffed’ with food references, on our screens and in our language, and Shriver’s book serves as an investigation into the Western obsession with consumption. In that regard, this hopeful, insane, self-fulfilling learning curve could have served as a ripping work of non-fiction by simply holding up the mirror.

But even Shriver admits to facing the very paradox she confronts Pandora with – trapped between her loyalty to a brother who has dead-ended his life by becoming grossly overweight, and her comfortable circle of attainment, complete with husband and career.

“As it happened, my brother’s condition abruptly plummeted again, and he died two days later. I never had to face down whether I was kind enough, loving enough, self-sacrificing enough, to take my brother on, to take my brother in. I got out of it,” Shriver wrote in The Financial Times on the book’s release.

When Pandora’s husband demands she make a choice between his fit lifestyle or the fat sibling, she eschews her marriage and embarks on a year-long, weight-loss odyssey that is Shriver’s imagination given free reign and healthy abandon.

Knowing the factual roots of the story only makes Big Brother’s pathos more powerful, because ultimately what Shriver construes is a startling piece of fiction, as unsettling as Tim Winton’s The Riders and every bit as capable of blindsiding readers.

The greatest part of the telling, for me, was not the exploration of weight but the surveillance suggested by the doublespeak of the book’s title, because Pandora’s solution for Edison is as Orwellian as its possible to be.

Despite being powerfully written in observational first-person, it’s in the minutia between siblings and spouses, unbridgeable even between those who ought to be close, that Big Brother makes the strongest claim on the human heart. See if you can keep it down.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.

This article appears in Michael’s eBook Creating Waves: Critical takes on culture and politics.

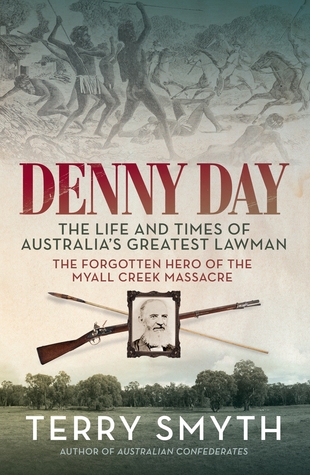

Terry Smyth’s

Terry Smyth’s