A Writer’s encounter with Britain’s boundaries.

ON the property where I grew up, porous volcanic rocks covered a little peak near the farm-house, the hundreds of holes in their sides the perfect dwelling place for the fairies we imagined lived there. Hours of exploration ensued on that hillock, from which the edges of the wider world could be seen, but not yet explored.

For exiled Europeans living in the pastoral dream of New South Wales, stone boundaries and homes were a link to the lands we had come from. The Northern Tablelands are scattered with flints, shales, and granite boulders. In parts, where the scrubby trees are scarce, and the skies large, you could swear you were on the Yorkshire Dales.

So when the opportunity to produce a program about dry stone walling came up, I leapt at the chance. The directive included the name of artist Andy Goldsworthy, who could be credited with taking the ancient craft and making it into a fine art.

We turned first to the Yorkshire Dales Field Centre, where Master Waller Stephen Harrison taught weekend courses in walling for anyone wanting to have a go.

This was the dawn of the reality show era, and it was suggested that we find a television presenter to send on one of these courses, to ‘throw them in the deep end’. We approached Dylan Winter, a country-based broadcaster. He was willing, we set a date in the Dales’ village of Settle, and went to build walls.

Cameraman Alan James got to ride in a hot air balloon filming the network of walls across part of the Dales. We went to an all-day walling competition. The whole thing was so much fun it hardly felt like work!

The true art of dry stone walling is in the word ‘dry’ – Stephen showed us places on the high ridges of the Pennines where walls had been built and maintained over centuries which you could kick and not make a dent in, yet they stood without a trace of binding mortar.

Very often there is little sign of human habitation, apart from the walking track, and then you’ll crest a hillock and suddenly see lines of stone – barriers – running across everything in their path for miles and miles.

The beauty of stone walls belies terrible times in the nation’s past – Hadrian’s Wall in the north might not technically be mortar-free, because it was built to keep people out of England, but dry stone walls are also evidence of a great ‘keeping out’ movement.

It was almost four centuries of Enclosure Acts that fenced-off the shared common lands of the countryside, starting in and around villages, but extending over time across every patch of farmland. Eventually the entire landscape was owned by someone, and it was walls (or hedgerows, where stone was scarce) which marked where the boundaries were deemed by law to be.

Men and women who once worked common land found themselves fenced out of it. Many eked-out new livings on the crews who built the walls. It’s a skill which has been handed down through generations.

Sourcing archival images and footage of walling crews at work in the early 20th century proved an adventure in itself, but between the libraries of the Lake District, and private collectors, we unearthed some very unique footage for our program. The interesting thing about the photographs in particular is how they revealed walling was a family pastime – men, women and their children were taught to wall in certain communities.

Stone is an effective barrier – if used correctly it can halt flood or fire, it looks better than barbed wire, and it’s not hard to work with.

Which is the message Stephen Harrison and the Yorkshire Dales Field Centre were keen to spread to city slickers like us. Dylan made some classic errors in his section (or ‘stint’) of wall, but, as Stephen pointed out, even a flawed wall will outlast most modern wire fences.

We travelled to Cumbria to meet Andy Goldsworthy’s assistant at an agreed time in a remote pub car park. She led us up into the foothills nearby, to a sheepfold – a square or round enclosure of stone designed to pen sheep. Andy was nowhere to be seen, but his work, on that occasion an arrangement of straw on the ground inside the stone enclosure so that it would catch the light from different angles, was incredible.

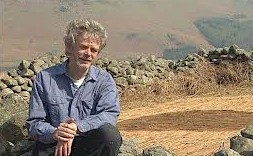

We all drew breath. Someone said “wow”. I noticed a scrap of woolly grey from behind the wall at the far side, and thought perhaps it was a stray Herdwick sheep, but when the sheep stood up it revealed itself as the artist.

“Good reaction,” he said, before I told him I thought he had Herdwick-coloured hair. He laughed, and within the stunning setting of a Cumbrian valley, we interviewed Andy Goldsworthy about his work with dry stone walling, and dry stone wallers, particularly on the long-term Sheepfold Project of the 1990s.

Stephen Harrison is one of a group of British wallers who regularly work with Andy Goldsworthy on art projects both in Britain and North America, but the boundary between artist and waller is invisible. Goldsworthy started out a farm boy, after all, and Harrison is very much an artisan in his own right.

Very often they build stone structures (not always walls) in art galleries. More regularly they’ll work in farm land, or in the wilderness.

In addition to Cumbria and Yorkshire, we interviewed wallers in Wales, Scotland (where walls are known as ‘drystane dykes’), and Derbyshire. In each region the stone varies in colour and density – in parts of Wales you can chop it with your hand, in some places around Scotland you can barely break it with a hammer.

I can’t think of a more accessible way to participate in ongoing heritage than to repair or build your own dry stone walls. As soon as I had my own garden I started, and I learnt that if you follow a few simple guidelines, anyone can seem like they’ve been walling for years.

Dry Stone Country is distributed on DVD by BecksDVDs.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.