A PLACE CAN be described as having a rich local writing landscape when its Indigenous language is being revived to ensure storytelling is handed down; when it produces an international classic that showed New England to the world, and when a new local-set novel is up for one of Australia’s biggest literary awards.

Traditional custodians of the Glen Innes region are the Ngarrabul people, and Ngarrabul yinaar (woman), artist and teacher Waabii (Adele) Chapman-Burgess explains what her people share about traditional storytelling.

“We disclose our Dreaming stories to pass on imperative knowledge, cultural values, traditions and lore to future generations,” she says.

“Aboriginal spirituality does not think about the ‘Dreaming’ as a time past, in fact not as a time at all. Time refers to past, present and future, but the ‘Dreaming’ is none of these.”

Chapman-Burgess has a Masters in Aboriginal languages and says Ngarrabul Dreamings are passed on through customs such as ceremonial body painting, storytelling, song and dance.

“I do this through my teachings of cultural awareness at school, teaching the local language to all our students,” she says.

According to Chapman-Burgess, this education process relies on archival material in university collections, audio recordings of older Ngarrabul people, and the documentation of selected Ngarrabul language by John MacPherson, a doctor who practised in the region from the 1890s until 1901.

“If it wasn’t for him communicating with Ngarrabul people at the time, we wouldn’t have the records we have,” she says.

There are a few Dreaming stories in Ngarrabul culture, Chapman-Burgess explains, including one about how the waratah turned red, and the Boorabee (koala).

Her personal connection to Ngarrabul country and cultural storytelling is, “about what you inherit and those birthrights handed down from family,” she says, adding that elders play a critical role in this process.

“They show us humility, their wisdom and their lived experience, and how to navigate the world.”

‘A man who had a cross’

Settler storytelling in the Glen Innes region invariably places a focus on D’Arcy Niland (1917-1967), author of The Shiralee, his first novel, published in 1955 by Angus & Robertson. The story of a swagman shearer, Macauley, who takes his young daughter ‘Buster’ on the road, the novel opens with plain talk:

“There was a man who had a cross and his name was Macauley.

He put Australia at his feet, he said, in the only way he knew how. His boots spun the dust from its roads and his body waded its streams. The black lines on the map, and the red, he knew them well. He built his fires in a thousand places and slept on the banks of rivers. The grass grew over his tracks, but he knew where they were when he came again.

He had two swags, one of them with legs and a cabbage-tree hat, and that one was the main difference between him and others who take to the road, following the sun for their bread and butter. Some have dogs. Some have horses. Some have women. And they all have mates and companions, or for this reason and that, all of some use. But with Macauley it was this way: he had a child and the only reason he had it was because he was stuck with it.”

Reviewing the book on its release in the Melbourne Argus, Gordon Stewart called it, “one of the most delightfully touching, yet virile stories of Australian character and the Australian bush yet published. And D’Arcy Niland is a writer who, with a little more polish and experience, will certainly cause some of the local literary luminaries to try their laurels again for size.”

Despite five further novels, Niland never quite rose to “luminary” status, partly due to his sudden death at the age of 49, the result of a congenital heart condition.

Arguably, his greatest achievement was attaining a writing career in the first place.

J. S. Ryan’s Tales from New England (Woodbine Press, 2008) includes a detailed analysis of Niland’s New England roots and The Shiralee’s connection to the region.

Born into an Irish Catholic family, Niland’s “nurture in Glen Innes in a modest and even unlucky family promised D’Arcy little more than labouring or shearing shed employment. Yet his early attempts at writing were much encouraged by Sister Mary Roch, one of his teachers at St Joseph’s School,” Ryan wrote.

A school leaver at 14, a copy boy for The Sun at 16, Niland had a very long road to the global acclaim he attained at the age of forty when The Shiralee was adapted for the big screen in 1957. Even after marrying New Zealand journalist and author Ruth Park (1917-2010) in 1942, he was still shearing in country areas to assist the war effort, while she was in the city giving birth to their children.

Marriage nurtured both literary careers, since the couple forged a strong unit permanently engaged in the graft of earning money from writing on many fronts: journalism, poetry, radio plays, short stories and novels. Her most enduring was Harp in the South (1948), an exploration of the Irish Catholic experience in inner Sydney.

Niland’s obituarist wrote: “In 1953 he had his first real break when he was awarded $1,200 by the Commonwealth Literary Fund to write a novel.”

That was The Shiralee, but one of Niland’s most overlooked works monetised his hard-earned craft, Be Your Own Editor: How to Make Your Stories Sell (Angus & Robertson, 1955). Both seminal titles emerged in the same year.

“A writer must have a capacity for gruelling labour, not sporadic, but consistent,” he wrote in this early example of the self-help guide. “He must have energy, grit, and perseverance. He must learn to be unwanted. He must learn to be lonely. He must learn to suffer despair and conquer it. He must learn to put up with jibes, misunderstanding, jealousy, but he must keep on writing.”

‘The most violent woman in Sydney’

Glen Innes takes centre stage in the first act of Fiona Kelly McGregor’s Iris (Picador, 2022) a novelisation of the life of Iris Webber (1906-1953) which was shortlisted for the 2023 Miles Franklin Literary Award.

The notorious busker, petty criminal and sly-grog trader grew up in Glen Innes as Iris Eileen Mary Shingles, before departing for Sydney in 1932, where she joined the same gangster underworld as Tilly Devine and was pursued by police for two decades, including trial and acquittal for murder.

McGregor researched the myths about Webber and found, “a story of poverty and struggle, and great tenacity and spirit and intelligence” as she relates on the Miles Franklin Award website. Her aim was to explore the person described by a police prosecutor as “the most violent woman in Sydney” (The Advocate, 24 April, 1948).

The first sections of the novel are set on the streets of Glen Innes in the 1920s and slightly earlier. McGregor places Webber, her mother, siblings and a father figure in a cottage at the south end of Grey Street, eking out an existence as domestic servants and lamplighters. In chapter two, Iris has her first encounter with guns:

“He took me to the end of our neighbour’s paddock, set an old kero tin on a fence post and handed me the Winchester.

Hold it like this. Look at the target and squeeze the trigger.

I got the tin first go. Pa Thomas was delighted. He set up another target and handed me the shotgun. This one’s heavier, he said. Firm against your shoulder, that’s right.

Pow. I got that one too.

You’re coming rabbiting with me tomorrow morning, champ. He tousled my hair.

I was the happiest girl in the world.”

Traversing the tension between the ‘happiest girl’ and the ‘most violent woman’, McGregor’s novel was described by reviewer Declan Fry in the Sydney Morning Herald as, “a brawling, picaresque book – ribald, clamorous, bruising; the work of an author who is having fun and who has kept going … kept creating.”

‘My desk in the highlands’

Glen Innes-born freelance writer Amanda Woods has lived in Sydney and London for most of her adult life, “but I love living back in the New England highlands and telling people around the world about Glen Innes,” she says.

“It feels great to be able to share stories from my corner of Australia in national and international publications and to be known by editors as a writer who really knows what it’s like to live in the countryside.”

Woods collaborated on Rock Pools of Sydney (Australia Unseen, 2022) with photographer Vincent Rommelaere, capturing the stories of well-known and hidden swimming spots along Sydney’s coastline.

A highlight in that book is Woods’ interview with the Buckettes, a womens’ group whose tradition of daily dips at Mona Vale’s Rock Pool created enduring friendships. The photographer and author are currently working on a follow-up, 100 Sydney Beaches, which will be released in late 2023.

A sought-after travel writer, Woods was educated at Emmaville Primary and Glen Innes High, before studying communications at Charles Sturt University.

“Being away from the big smoke offered a lot more time to read and to be with your own thoughts,” she says.

“But it also gives me the gift of a peaceful working environment where I wake up to the sound of magpies rather than construction work or traffic, which were a constant soundtrack in Sydney.

“I feel lucky to be surrounded by fresh air and good people in Glen Innes and as much as I need to write when I’m on the road, I prefer to save my writing for when I’m back at my desk in the highlands.”

‘An unbroken chain’

Plenty of other writers have worked at desks in these same highlands over the decades, or taken their experiences of the region into writing careers. It would be impossible to find every one who has been inspired by Glen Innes, but a selection shows the breadth of subject matter.

According to her obituarist Lynne Cairncross in the Sydney Morning Herald, food writer and journalist Margaret Fulton (1924-2019) went from Girl Guide campfire cook in Glen Innes to the author of the 1968 bestseller, The Margaret Fulton Cookbook, becoming “a household name” whose “books lived in almost every kitchen in the country”.

Emma Mactaggart, prolific children’s book author and publisher, is a driving force behind the Child Writes program, an initiative that supports young people to write books. Her Child Writes: A Step-By-Step Guide to Writing and Illustrating a Children’s Picture Book (Boogie Books, 2015)was one of the first Australian texts about the independent publishing process for Australian authors.

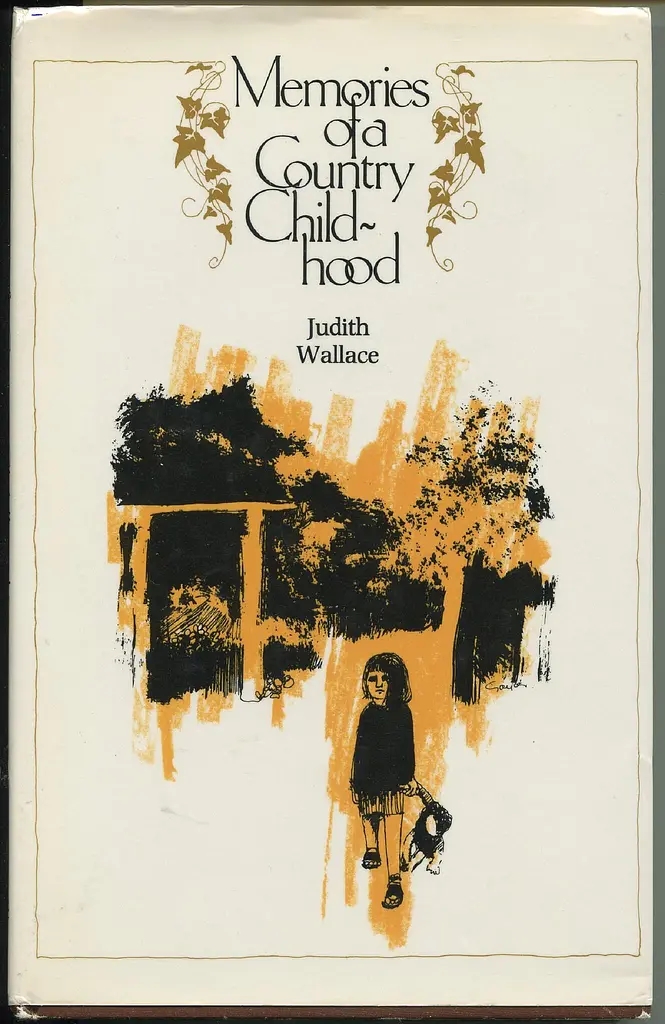

Judith Wallace’s memoir Memories of a Country Childhood (University of Queensland Press, 1977) recounts life on “Ilparran”, her family’s property west of Glen Innes, during the 1930s and 40s. It opens with a reminder about time:

“Both the house and the garden seemed old. They seemed to stretch back endlessly into time. The portraits on the walls of the dining room were of people who had lived thousands of miles away as well as hundreds of years ago. Time and distance blended together to form “the past”, and the past was linked in an unbroken chain to the present. England was ‘the past’, Australia ‘the present’.”

Ngarrabul woman Elena Weatherall is a writer who grew up in Brisbane and now lives and works in Glen Innes. An untitled poem from 2017 was inspired by a visit to the Common on the western side of the railway line where Indigenous people once lived. The work is dedicated to Weatherall’s mother, Leonie, who with her parents and siblings were the last family to move off the Common.

Its final section explores similar themes to Wallace’s:

What can I do to keep my culture alive,

How can I prosper, cultivate, survive.

The answer still lost or left for someone else,

Who may just happen to find themselves,

At the edge of a creekbed, dry from no rain,

Where families lived but now none remain.

“I’m grateful to be back on Country, and to give back to the community,” Weatherall, a family and youth support worker, says of Glen Innes.

“I’m home again, I never want to leave.”

This article was first published in the Glen Innes & District Historical Society’s annual Bulletin, 2023. Main image: Rebecca Smart and Brian Brown in The Shiralee (South Australian Film Corporation, 1987)