WITH nothing more complex than a series of firmly closed doors, the film Carol takes a powerful dramatic turn that subtly gives two women the space to explore their attraction.

“The wait for enlightenment will be long, and the darkest, pre-dawn hour lies ahead.”

When Therese (Rooney Mara) slips into the passenger seat beside Carol (Cate Blanchett) and shuts out her fiancé, they leave him blinking on the kerbside. Soon after, Carol’s old flame Abby (Sarah Paulson) firmly shuts her front door on Carol’s estranged husband (Kyle Chandler), leaving him awkwardly framed through a small window.

But it is the shutting of the door between the two protagonists – closed by Carol against Therese at the height of an argument – which makes forbidden fruit all the more potent for both women.

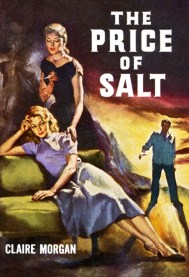

Phyllis Nagy’s screenplay (based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt) uses these pivotal separations to mark out the territory of a love story that breaks several taboos.

The shutting-out of men has been a powerful literary force ever since Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) in which Helen Graham dramatically slams her bedroom door in her husband’s face and created what many credit as the first feminist novel.

Published a century later, and phenomenally successful in its day, The Price of Salt disappeared from mainstream lists until Highsmith came out as its author in the 1980s and changed the book’s title. Plans were made in the 1990s to adapt it for the screen, and almost twenty years on – surely one of the film industry’s greatest examples of persistence – the story has been thrust into mainstream consciousness.

And its arrival pulls few punches. The unstable yearnings of unfolding passion will be familiar and understandable to anyone who has ever fallen in love, but emotional and sexual lust between two women is rarely seen on the big screen across suburban cinemas.

Carol contains several quite inadvertent similarities to other stories. When Carol and Therese take to the road, the story has strong echoes of Thelma and Louise. The escapist quality of that journey also speaks to the kind of concealed passion explored in Brokeback Mountain.

Highsmith’s novel traverses similar tragic precipices, yet its originality lies in the choices Carol and Therese make when their love is swiftly and coldly thwarted. Far from home, in a frozen place ironically called Waterloo, they have the door to their world cruelly wrenched open for the very worst of reasons – a blow that lands right in Carol’s weak spot.

It is from this point in the story, the final act of Carol, that Phyllis Nagy has done greatest service to Highsmith, but don’t be fooled by the alleged ‘happy ending’ tag this story has garnered. While it doesn’t have the shock ending of Thelma and Louise or the tragedy of Brokeback Mountain, the denoument of Carol comes with a level of compromise and risk that could never be defined as a positive outcome.

Cate Blanchett portrays Carol as glamorous and anaesthetised, at times a sheer minx and at others world-weary, as though every stroke of make-up and hair product in the high-fashion front is only just managing to hold her upright. She inhabits Highsmith’s title role with a languid style that is never more poignant than when Carol is required to behave.

The slow burn of Therese’s story is given a sparse amount of dialogue, since her passion must remain internal until it is safe to express. Rooney Mara gives Therese the perfect hyper self-awareness in the role that is closest to Highsmith herself, who revealed in the book’s 1989 re-release that she’d encountered a woman like Carol while working in a department store as a youth. Despite finding out where she lived, Highsmith never made contact.

Knowing the fully fledged rage with which Highsmith went on to live and write by, it’s impossible to watch Rooney Mara’s performance without the sense that Therese would eventually give Carol a run for her money as a self-determined woman.

Haynes has been praised for the visual style of Carol, yet it has nothing like the luminous, throbbing-with-colour quality of his other 1950s-era film Far From Heaven (2002).

Carol and Therese inhabit a darkened, soft-focus, wintry world. Glimpses of sun show themselves at the edges, but remain out of reach, as though the wait for enlightenment will be long, and the darkest, pre-dawn hour lies ahead.

Nagy’s screenplay achieves far more with the story’s dramatic turns than Highsmith’s novel, which was her second and suffers a little from not knowing what to do with these characters before she sets them on the road.

Nagy knew Highsmith and drew on her friend’s experience of what it was like to be a lesbian in the 1940s and 1950s by adding detail on the legal and psychological challenges faced by same sex-attracted women in the United States.

But Highsmith’s novel sends Carol and Therese on a journey through America’s road culture, beyond the restrictions of their lives and dangerously oblivious to the ramifications of their journey, that is not fully realised on the screen.

“A mesmerising, disturbing film about unearthing passion and controlling rage.”

The scale of the route rivals that of Thelma and Louise, yet the cinematic potential of vast landscapes is not captured in the film. When the city-dwelling protagonists emerge in an expansive, elemental space they are unlocked from the world that confined them, and their enemies are required to do far more work to rein them in. In this, Carol is a precursor to Highsmith’s best-known works, the Tom Ripley series of thrillers, and leaves the novel worth reading for its own sake.

A mesmerising, disturbing film about unearthing passion and controlling rage for the sake of relationships, Carol explores the limits of what people will accept and the territory they will not negotiate.

The right to evade capture, to avoid being shut out emotionally, are portrayed as loudly as the sexual criminality of the era, and make a universal story out of what might otherwise have remained a period piece.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.

This article appears in Michael’s eBook Creating Waves: Critical takes on culture and politics.

The stories in Closet His, Closet Hers illustrate this kind of prejudice. All the Worst Jobs is the story of a lesbian care worker, Jessie, who is outed by the older woman she showers every morning. The risk for Jessie immediately increases at this point, since she relies on the income yet walks the knife edge with her client, who seems to hold all the cards.

The stories in Closet His, Closet Hers illustrate this kind of prejudice. All the Worst Jobs is the story of a lesbian care worker, Jessie, who is outed by the older woman she showers every morning. The risk for Jessie immediately increases at this point, since she relies on the income yet walks the knife edge with her client, who seems to hold all the cards.