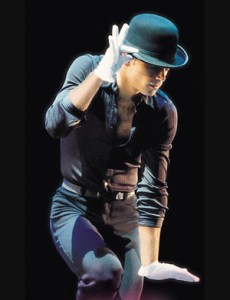

ONE random night in 2004, Michael Burge’s long-term partner, choreographer Jonathan Rosten, died suddenly while rehearsing a show.

In the midst of the ensuing grief, Jono’s relatives started the secret and devastating process of disenfranchising Michael from his position as Jono’s next of kin.

Unable to wrap-up his de-facto partner’s affairs, in a legal, ethical and financial ‘David and Goliath’ battle, Michael was exiled from his own life, facing grief, depression and suicidal thoughts.

The story of how he found the strength to right the wrongs is told in a new book.

An extract from Questionable Deeds

“A tough but ultimately triumphant and deeply satisfying read. It touches on themes of grief, denial and injustice. The ending is uplifting.” – Mary Moody.

“You know that your partner’s heart has stopped?” he asked me in a careful tone.

I said: “Yes”, waiting for the next part about them rushing Jono into surgery.

“Well,” the nurse said, “we’ve been unable to start it again.”

My hand went to my face, but it hit me on an angle. I didn’t care, I thought I was slipping off my chair. People seemed to be rearranged in their seats by unseen forces as I left the nurse and Jono’s old friend Amanda behind.

I was led into a corridor, where I watched how another nurse pushed a red button to open opaque glass double doors. Behind that, in a curtained space, Jono was lying still on a gurney under a sheet.

It is true what they say about the newly dead appearing to sleep. Jono’s face was relaxed, his skin pliable, as I brushed my hand across his forehead, the sobs starting to run through me like tremors. I felt the silkiness of his eyelashes as I kissed him.

Not yet believing, I opened one of his hazel eyes, and the gaping darkness of his dilated pupil met my gaze; a sudden wall against the life here, the emergency department of a Sydney hospital, and wherever he now was.

“The room was about to fill with strangers it would take me hours to free myself of.”

My glance must have been like a scan, both forensic and feeling. He was just so beautiful, a perfect version of himself, with his body’s tendency to slump slightly sideways, chin dropping to his left shoulder, the way he’d always done in life in moments of vulnerability and cheekiness.

But the worst thing of all had happened to him, the very worst. The eyes told me that.

The green sheets around his naked body concealed all trauma, apart from the point at the top right of his chest where an intravenous main line had been inserted in an attempt to save him, and two small grazes on his nose and cheek where he’d knocked himself as he’d fallen to the floor, alone, in the rehearsal room.

But all that knowledge was to come. In that precious, solo moment I took in the reality of Jono’s death.

“I will cry for you for a very, very long time,” I said, my loneliness coming back at speed.

Acceptance did not take long. Resistance to it is useless. I read years later how, faced with this moment, Yoko Ono had repeatedly smashed her head against the tiles of the hospital wall.

For me, the moment was filled with the memory of the grief of losing my mother at a young age, although I had the cold sense of how very much worse this was going to be.

I instinctively ran my hands over Jono’s arms, his belly, and cupped his penis in one hand through the sheet, bidding those intimacies farewell. After not very long I tried to return to the hallway, through the automated doors.

But I found myself trapped in the corridor. The exit to the waiting room was one way into the life to come. Jono, and our life together, was in the other direction. When I chose to go back to him, a passing nurse came across me in my indecisive confusion, and pushed the button for me.

I went back to him for a moment. I don’t know why. To see if it was true? It was. I don’t remember anything about the next moment of separation, the walking back outside.

I sat down in a new room, and a young man, a counsellor, introduced himself to me. I needed to make some calls. I tried my sister Jen. There was no answer. Amanda stood and hugged me, told me how sorry she was. For a moment, sitting in my chair, I was suspended in the naphthalene scent of her fur coat.

Somehow I was made aware that Amanda was going in to see Jono, but I made no objection. I was in shock. The reality of Jono’s death was being transmitted across the city. The room was about to fill with strangers it would take me hours to free myself of.

It never occurred to me that nobody in that place, apart from a medical practitioner, or me – Jono’s partner and senior next of kin – had the right to view his body. His naked body.

Because I was unaware that my relationship with Jono was not ours alone. I had no idea in those precious, vulnerable moments that he and I were well and truly owned.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.