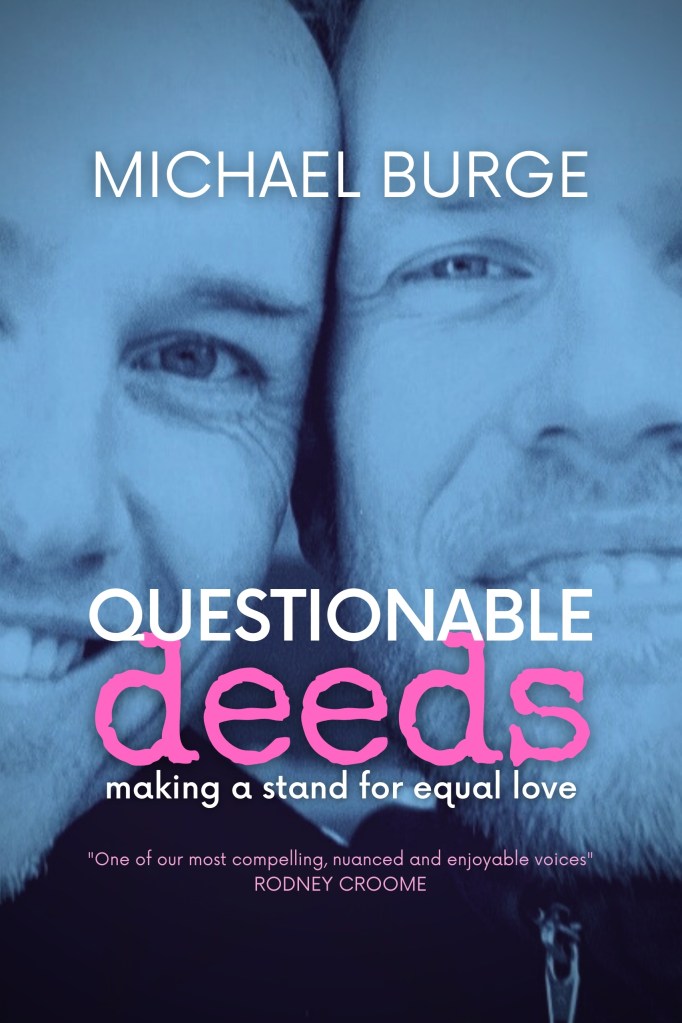

IRELAND’S yes vote for marriage equality kicked a rainbow-coloured goal for LGBTI people around the globe, and while the major Australian political parties fight for ownership of the ball, this extract from an upcoming podcast and book Questionable Deeds is a reminder of how far we’ve come.

IN the lead up to the 2004 federal election the issue of same-sex marriage hit the media.

The year prior, various provinces followed Ontario’s lead in Canada and allowed same-sex marriages to take place. Many Australians availed themselves of this legislation since it did not require the couples to be residents, but as soon as the newlyweds stepped back onto Australian soil, the marriages had no legal standing whatsoever.

Two couples decided to test Australia’s Marriage Act (1961), and their application landed on the desk of federal Attorney-General Phillip Ruddock, sending him into a spin.

“Marriage, like a seed, was planted within me.”

It turned out there was no specific mention of gender in the Act. As far as the law was concerned, any two people, same-sex or otherwise, could apply to be married in this country. Back in the early 1960s when the legislation was created, nobody even dreamed of same-sex marriage.

The conservative Liberal government, led by John Howard, went into overdrive to see this loophole changed, and they got plenty of support from both sides of parliament, election year or not.

By August of the year my partner Jono died, same-sex marriage had been made a legal impossibility in this country. I barely recall the announcement. It would have passed through my consciousness in my deepest grief and registered only as another reason to feel dreadfully unsafe about being same-sex attracted in my own country.

The looming election, of course, required me to turn up at the ballot box, since all Australians must have our names ticked off the voting register on the day, whether we use our vote or not.

The voting queue at the local primary school, the same one I had attended over twenty years’ prior, was long. It gave me plenty of time to think over the issues, and, more importantly, to observe people and the colour of the how-to-vote cards in their hands.

Prime Minister John Howard was showing great leadership for the majority of Australians – sixty per cent – who objected to same-sex marriage, and, by the amount of blue of the cards I saw all around me, things were not about to change.

They didn’t. The diminutive target John Howard saw off the Labor party’s brutish Mark Latham, no problem.

But marriage, like a seed, was planted within me as a concept. Alone, processing the loss of my partner, I pondered what difference marriage would have made to my situation.

First and most obvious was the certification. The warranting of a relationship’s existence is so easy with that ‘one piece of paper’ which straight couples had access to for years prior, eschewed by many as either too binding or not needed.

I realised how much simpler it would have been for me, one certificate, and how much harder – impossible, really – it would have been for Jono’s mother and brother to erase the visible signs of his relationship with me.

I thought of the traditional marriage vows, and the words ‘forsaking all others’.

I processed its meaning, looked deeper than any sublimation of women and property rights, to find how the line was actually a warning to all those present at a marriage ceremony that they are the forsaken ones. Their son or daughter is placing them on solemn notice with that line, warranting that they are no longer the next of kin to their loved one.

Their spouse replaces family, from that moment, and a new family unit is created.

My parents’ marriage had ended in acrimonious divorce, to the point where my mother was wary of any signs of my father in me and my brother, and our father allowed his new wife to demonise our mother as she saw fit.

I was glad they did not stay together, and Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s leadership on fault-free divorce through the creation of the Family Law Act (1975) had built the firm foundation that allowed many families to undo what needed to be undone, with access to legal aid and counselling.

Almost instantly I shed my wariness of marriage. I saw exactly how it could work for same-sex couples needing that line in the sand around our relationships, whether the marriage lasted forever or not.

Marriage did not have to follow the archetypal plan. Its history is littered with anomalies, of couples stretching its boundaries, simply because they were quite safe to do so by law. In recent times, any victim of marriage also had recourse to become un-married.

I recalled the night Jono and I took one another to our favourite pizzeria on Katoomba Street, on the brink of relocating to Sydney and starting a new phase of our lives. Jono was pensive until he revealed what was on his mind: he was worried that he did not have enough to offer me as a partner, being ten years my senior. He wondered if I wanted to explore other relationships.

I looked him in the eye, and held his hands between mine, and said: “No, Jono, that is not what I want. I want to be with you.”

He bent his head in his humble, accepting way, flicked the corners of his mouth up, and we kissed.

From that moment, we were married. The only things missing, apart from the support of any law, were two witnesses and a state-sanctioned celebrant.

Widowed and alone in that voting queue, barely two years later, I became a marriage equality advocate.

An extract from Questionable Deeds: Making a stand for equal love.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.