A Writer drowning in words.

I’M proofreading my first two publications right now, and I’m aiming to complete around 140,000 words in under a week.

It’s an ambitious task and thankfully I have some assistance, however, as an independent publisher (a fancy way of saying ‘self-published’, which carries a terrible stigma), this is my self-inflicted creative penance.

Cue the violins! Independent publishing is not all it’s cracked up to be!

“It’s no wonder everyone’s avoiding checking their own work – it was always a relatively crap job.”

Sure, it’s liberating when you don’t have to run decisions past anyone, but when it comes time to hit that publish button, where the quality of the finished product is concerned the buck stops with you. What’s worse it that although they pay very little for our books, quality has very high value placed on it by our readers.

If you’ve ever watched TV talent shows you know how risky stepping into the limelight can be for singers who have not been massaged into the public gaze by management and stage training. Quality comes across only when contestants have a decent amount of singing ability.

How cringeworthy is it when wobbly performers compete week after week slightly off pitch or rough on the high notes? It doesn’t mean they’re not talented, but it’s almost a relief when they get voted out, leaving the stage to more assured vocalists.

Art is a bitch that way, and writers have all the same potential to seem extremely unattractive in the public domain. No matter how schmick our book’s cover or what publicists we’re tempted to pay, we are prone to get voted off in the first paragraph.

Part of being match fit is ensuring our words are the best they can be, which means either paying for copy editing and proofreading, or doing it ourselves.

I’ve chosen the latter, because I have the skills, but this week I have wondered if this was the wisest course of action.

All writers have patterns. We use language in wildly different ways, and, despite appearances, there is no one language standard when it comes to the written word.

My particular weakness is hyphenation. If I can manage to slip-in an inappropriate or un-necessary hyphen, I will.

Yes, we have spell check and grammar guides in our word processing software, but do you know which standard of which language yours is set on, and have you ever tried to change it?

Yes, there are dictionaries, but have you ever wondered how many?

The factual answer is nobody knows, but that doesn’t stay the judgmental hand of the average Grammar Nazi, who I imagine scanning free samples of eBooks instead of buying them, seeking out the errors as a form of bloodsport.

The factual answer is nobody knows, but that doesn’t stay the judgmental hand of the average Grammar Nazi, who I imagine scanning free samples of eBooks instead of buying them, seeking out the errors as a form of bloodsport.

Language is an organic, ever-changing entity. To successfully proofread something, writers need to accept that they’ll capture the language they’re using for a brief moment before it continues its evolution.

If you decide to DIY your book’s proofreading, doing so consistently within that moment is your job, and that’s the really hard part, especially for the generations of writers who were not taught grammar at Australian primary or secondary schools from the 1970s, when it was deemed unnecessary, a directive that continues to this day.

I know several writers who claim to be unable to proofread their own output – journalists, mainly, who’ve had the luxury of sub-editors for decades.

But sub-editors are being shafted by media organisations across the English-speaking world, leaving journalists to proof our own articles.

It’s no wonder everyone’s avoiding checking their own work – it was always a relatively crap job that should be royally paid for, when at its core it’s basically clearing up the shit written by others.

I have one tip for writer-proofreaders aware of the reality that self publishing is expensive – shut the windows, put the cat out, tell your partner not to come knocking, and simply read your work so damned well it’s like the last time you’ll ever read it.

And I have one tip for writers willing to pay for proofreading – no matter how much you pay, it’ll never be perfect.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.

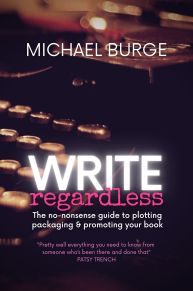

Check out Michael’s book on indie publishing.

Creating and sending multiple pitches can get very boring. Have some fun and break the rules a little. I recently sent a pitch to a publisher who said “no unsolicited material”, and they looked at it! Doing this each and every time is probably not a great way to get a book published, but now and again, mix it up. There is really nothing to lose when you think about the crazy odds of the publishing trade.

Creating and sending multiple pitches can get very boring. Have some fun and break the rules a little. I recently sent a pitch to a publisher who said “no unsolicited material”, and they looked at it! Doing this each and every time is probably not a great way to get a book published, but now and again, mix it up. There is really nothing to lose when you think about the crazy odds of the publishing trade.