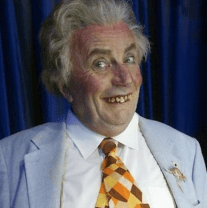

OVER many late nights during my last year of drama school, overworked head full of theatre productions, closeted young body starved of sex, I came across Alan Bennett on the television screen.

Volume down very low so that my grandmother (with whom I lodged) would not be disturbed, I encountered Patricia Routledge, Maggie Smith and Julie Walters in their now iconic episodes of Bennett’s first Talking Heads series.

Bennett remained the cursory sketch of the opening credits until the episode in which he appeared – A Chip in the Sugar.

The tale of the hapless Graham Whittaker living with his ‘Mam’ in Yorkshire drew me into its closeted fold, where I recognised absolutely everything about the character’s world, right down to the old woman sleeping in the room next to mine.

“Alan Bennett keeps explaining what’s behind his writing style, it’s just that no one’s really been listening.”

A month after I was born, the great writer E. M. Forster died publicly closeted despite reaching the era in which homosexuality was decriminalised in England. His gay-themed writing was entrusted to friends and took time to come to light.

He’s rarely comfortable admitting it, but Alan Bennett is something entirely different. Yes, the first thirty-six years of his life were lived under laws against homosexual acts between men, but these days he’s a right here, right now gay writer and actor, infinitely closer to generations of men easing our way out of the closet than Forster ever was.

Although back in the 1980s, nobody seemed to question Bennett’s ability to create characters on a scale E. M. Forster only dreamt of.

The most infamous query came from Ian McKellen, who asked the playwright publicly whether he was gay or bisexual at an event raising funds to fight Thatcher’s homophobic Section 28 regulations in June 1988.

Fifty-four at the time, Bennett’s answer left him rather begrudgingly out of the closet ever since.

But that news didn’t reach Australia, not in my world anyway. It did not need to – I could tell by the ‘takes one to know one’ method that Bennett was not just acting like a gay man in A Chip in the Sugar.

Although that realisation meant that I was going to have to do some clever acting of my own to put people off the scent of the truth.

Writing this now I feel of a kind of rage that a gay drama school student did not feel validated by Bennett’s achievements.

Instead, it left me afraid, with the sense that there was nowhere to hide; that all gay men were bound to the apron strings by the kind of fear which Graham Whittaker manifested as mental illness. It offered little hope for those men who did not stay silent.

Perhaps that’s why I disconnected from Alan Bennett for a decade, during which I lived in England and did my level best to become a theatre and film-maker. ‘Gay’ was kept at arm’s length, and I got certain very specific signs that I needed to keep it there.

The most direct of these came during my year of drama training in Yorkshire (Alan Bennett ‘country’) when I was taken aside by one of the pivotal staff members and told that I needed to curb myself or the work I would get on graduation would be “limited”.

His admonishing tone about my natural demeanour came, as it always seems to, with the “I’m only saying this to you because I know plenty of gay people” lie.

By the time I’d gathered the courage to go home to Australia and come out, six years later, Alan Bennett made another appearance in my life, in the form of his memoir Writing Home.

The book was given to me with an unusual amount of sadness by one of the many male friends I’d made in England who were soon to come tumbling out of the closet in the wake of my own coming out.

Bennett’s book helped me realise that being openly gay would not necessarily be an issue, but it would probably leave me more prickly than ever.

I have paid much closer attention to Alan Bennett ever since, but it’s taken another decade to understand the writer who constantly tells us that he does not want to be understood.

You see, Alan Bennett keeps explaining what’s behind his writing style, it’s just that no one’s really been listening.

One of his recent plays – The History Boys – is also one of his most popular, regularly featuring at the top of ‘Britain’s Favourite Play’ lists.

The story of a group of school boys preparing for their university entrance examinations, Bennett instilled this play with a major theme in his writing – authenticity versus artifice.

Ever since his own entrance into Oxford in the 1950s, Bennett has employed a writing technique which he used when answering examination questions.

He calls it “taking the wrong end of the stick”, a journalist’s approach to ‘the facts’. In entrance examination answers it can be utilised to impress with a new ‘out there’ angle on a subject that has been ‘done to death’; an attention-grabber, if you like.

This is also the key to the pathos in all Bennett’s work. His characters show pluck in the face of diversity. They laugh when it might be more appropriate to cry. They see obstacles as opportunities.

Good use of pathos is funny, not in the side-splitting sense but in the chuckling one. It’s right up the other end of the stick from turgid, and it totally avoids the branch of melodrama.

It took maturity, and an understanding of pathos, for me to realise that Gordon Whittaker’s salvation came with his mother’s admission that she had found his hidden gay pornography.

It is the great power shift in A Chip in the Sugar, when Graham’s ‘chip’ is seen as considerably smaller than Mam’s, giving the viewer hope that the result is a more accepting future for Graham.

There is some proof of this in Bennett’s recent writing. In A Life Like Other People’s (published in 2005 as Untold Stories) Bennett let slip that the mental illness he imbued Graham Whittaker with in Talking Heads (1987) was actually that endured by his real-life mother years before.

In the early 1970s, Bennett (‘Graham’) was torn away from a healthy same-sex life in London to care for his mother (‘Mam’) in Yorkshire.

Art stood in for life until Bennett ‘came out’ about the true nature of his family’s struggles with mental illness, thirty years after the fact.

So, ‘Graham Whittaker’ wasn’t in the least bonkers and went on to live a successful life as one of England’s finest playwrights and found love with a man. Phew.

Alan Bennett has published enough about himself for people to leave him alone about his sexuality, although in recent interviews he’s hinted at posthumous diaries which may come to rival E. M. Forster’s.

Alan Bennett has published enough about himself for people to leave him alone about his sexuality, although in recent interviews he’s hinted at posthumous diaries which may come to rival E. M. Forster’s.

He’s also managed to avoid the tag ‘gay playwright’ by taking the wrong end of the stick whenever one is offered.

© Michael Burge, all rights reserved.

This article appears in Michael’s eBook Pluck: Exploits of the single-minded.

Send it out again

Send it out again