TWENTY YEARS AGO today, not long after six o’clock in the evening, my partner Jonathan Rosten needed to take a seat during a rehearsal at a Sydney dance studio, complaining of a racing heart.

Very shortly afterwards, he collapsed. First-aid could not revive him, nor could paramedics. By the time I got to his side they’d been attempting CPR for almost thirty minutes.

He was bundled into an ambulance that rushed him away into a busy city evening at the end of a stunning autumn day, yet by the time I arrived at the hospital, he was lost to us all at the age of just 44.

Considering the fallout after one gay man’s untimely death, I’m compelled to look at what has changed since that last day of autumn in 2004.

Interrogation of a Nation

“What did they do to you?” Madeline asked me, sitting on the back deck of the house my husband Richard and I shared in Queensland.

That was the winter of 2013. By then, I was living a completely different life in a new relationship, a new state and a new profession.

I’d long tried to articulate the experience of being disenfranchised from my relationship with Jono by the very people who should have cared the most – his blood relatives – but had usually given up when people failed to understand why anyone would do such a thing.

Madeline didn’t demand an answer, she just listened.

The passage of time had ignited something in me, because hours later I still couldn’t let things go in my mind. Revisiting the worst period of my life was still a shock, and over the following weeks and months I started to piece together the awful truth.

Writing had always been my strongest suit, and for almost a year I recorded not just my experience of loss, but also the mutual gains that Jono and I had manifested in our relationship.

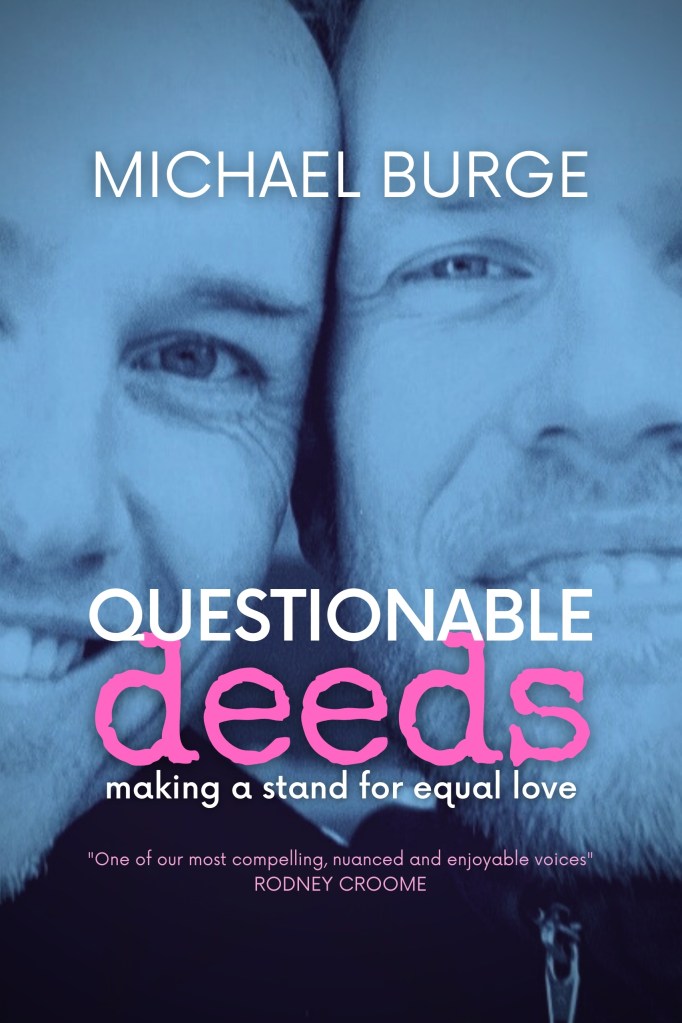

My memoir, Questionable Deeds: Making a stand for equal love (High Country Books, 2015 and 2021) was the long-form answer to Madeline’s question. It was an interrogation of a nation that was not acting in the best interests of same-sex attracted people, in fact it was making our lives worse; and it threw up just as many questions as it answered.

Piece of Paper

Marriage equality seemed so far off in 2004 that even significant sections of the LGBTIQA+ community didn’t get behind it. A Newspoll taken the month after Jono’s death showed support languishing at just 38 percent against 44pc opposed. The 18pc of undecideds were, ironically, deciding the status quo.

In my shock and grief that winter, it was a depressing show from my country. Even so, I became a marriage equality advocate overnight when I realised what a critical cultural statement it would make for same sex-attracted relationships to be upheld by law, whether we were married or not.

But for years I was forced to listen to those who reckoned de-facto relationship rights were enough, that the New South Wales legislative change in 1999 was all the cultural statement required. But my experience – five years after those laws included same-sex couples – showed that anyone, from disgruntled family members, funeral directors and public servants could easily rearrange the pieces of my late partner’s life to make it appear as though he’d never been in a relationship with me, stamping all over my rights in the process.

Same-sex equality campaigning eventually became a hallmark of my new relationship, and Richard and I marched the streets, knocked on doors, collared politicians and signed petitions because we understood that this country needed marriage equality at the earliest opportunity.

It was eye-opening to hear from those who wanted to uphold ‘the good old days’ when same-sex partners hid in plain sight for all kinds of reasons. Many feminists understandably upheld their anti-marriage stance, although this was a pro-equality issue.

Australians love a numbers game, and the public-vote approach forced on the country became about much more than marriage, it was about LGBTIQA+ dignity.

Across those years, it was painful to witness similar situations to mine still happening while the nation prevaricated under conservative leadership; but since December 2017, when Australia’s Marriage Act was finally altered to include same-sex couples, I haven’t heard of another case.

That’s not to say that blood relatives won’t try. I’ve heard of a few attempts to push a same-sex surviving spouse out of their senior next-of-kin status, but the “piece of paper from the city hall” that Joni Mitchell sang about not needing has held the line again anti-queer prejudice.

Ripple Effect

In a 2022 survey by YouthSense, 1367 Australian Gen Zs aged 15-24 were canvassed about their sexual orientation, and 32 per cent responded that they identified as LGBTIQA+.

YouthSense attributed this confidence in our queer youth in part to a ripple effect, after the majority of the Australian community got behind marriage equality.

This gives me a sense of pride, but I sometimes wonder what Jono would have thought of the person I’ve become. We often chatted about gay rights. Being a decade older, he reached his adulthood before homosexuality was legalised in NSW in 1984, and survived the frightening early years of the AIDS epidemic, but he usually took a lighter approach than I did.

After his death, I recognised his attitude in many queer campaigners who’d endured so much upheaval by the year 2000 that the idea of fighting on for marriage equality fatigued them. Jono turned forty in that year and was looking forward to a bit of peace and time to pursue his love of choreography, which is, ironically, what he was doing right up to his death.

Our case was heard by the Human Rights Commission in 2006. I spoke in front of the gathering and the media with a very wobbly voice that morning, due to lingering grief and shock, anxious because I was presenting my grief as a case study of the unnecessary extra angst that LGBTIQA+ were being put through when our loved ones died.

Subsequently, the commission produced its Same Sex, Same Entitlements report, which led to almost 100 pieces of discriminatory financial laws changing in 2010, another step in the long journey to alter the Marriage Act in 2017.

I’d made a stand, something I had never done before on such a scale and may never do again, and that was certainly worth writing about.

Creative Allies

Questionable Deeds still serves an important purpose for me. It’s re-traumatising to rake over the coals when someone asks about my experience. Being able to point them to a book means I can get on with my life while the reader’s awareness is raised through words on a page.

I’ve written since I was a teenager, although by the time I realised I was gay and entered a long period of closeting, it felt impossible to express myself in that way due to the fear of my secret being discovered.

By the late 1990s, all that changed, and I tentatively started writing more than scripts and marketing materials in my day jobs. The day that Jono died I was sitting at my computer working on a full-length play. In the fallout, it was a full year before I was able to find the peace and security to get back to work on it, but when I did, I noticed more significant changes.

No longer was I prepared to leave LGBTIQA+ at the sidelines of my subject matter. Long before the cultural shifts of marriage equality, I embarked on a journey to bringing cultural change to literature.

But literature took even longer to budge than legislation. In a skittish cultural landscape, my queer-themed play never found a producer, and Questionable Deeds did not land a book deal, although after I published it it was selected for the first LGBTIQA+ panel at the Brisbane Writers Festival in 2016 and became an Amazon bestseller.

It took many years to land my first book deal for my debut novel Tank Water (2021, MidnightSun Publishing). Because it deals with rural homophobia, I’ve been invited to literary events across the country to contribute to conversations around crime, justice and the change in LGBTIQA+ lives outside of cities.

After decades of being granted relatively easy access to jobs in rural-based media in the UK and Australia, by virtue of being born and raised in the bush, I was gobsmacked when, in 2021, the new Guardian Australia Rural Network approached me as a rural-based journalist to write and edit. The first subject matter they wanted me to generate coverage of was rural gay-hate crime.

Now, at long last, this thing called a writing career no longer feels like a solo journey, and with plenty of new projects in the pipeline I’m collaborating with more people than ever.

One of the most special aspects of my relationship with Jono was our discovery in one another of an ally for our creative endeavours. We had hours of discussion and planning for our projects, and I loved seeing the glow of inspiration rise in him.

I carry a bit of it still, because I know how such reciprocal validation feeds equality within a marriage. Perhaps that’s the ultimate lesson in marriage equality for everyone, not just LGBTIQA+.

Questionable Deeds: Making a stand for equal love is available from The Bookshop, Darlinghurst (Sydney); Hares & Hyenas (Melbourne); Shelf Lovers (Brisbane). and High Country Books.